Lower Wisconsin Riverway Receives Wetland of International Importance Designation

Jean Unmuth | Oct 27, 2020

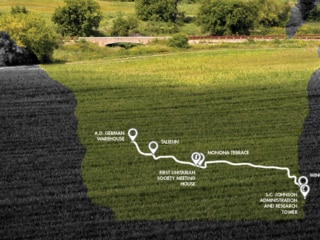

Discover the rich diversity of the Lower Wisconsin Riverway near Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin summer home and learn why the area was recently given such an important and prestigious wetland designation.

If you’re looking to view the explosion of fall color then head no further than the Lower Wisconsin Riverway which was recently recognized as a Wetland of International Importance by the United States and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. What is Ramsar? It is an international treaty that promotes wetland conservation and sustainable use. It does not impose any land use restrictions and has no regulatory authority. This designation follows the final 92 miles of the Wisconsin River from the Alliant dam at Prairie du Sac to the confluence with the Mississippi River near Prairie du Chien, and includes 44,000 acres within the riverway that are owned by federal and state agencies and the Ho-Chunk tribe.

Why is the Lower Wisconsin Riverway (LWR) Ramsar site so significant? At least one of nine criteria must be fulfilled in order to gain this status, and the fact that seven of nine criteria were met shows just how significant the site. Background data and analyses were used to support the criteria, including the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources 2016 LWR Master Plan, Important Bird Area studies, and the Wisconsin River Action Plan. The site includes more than 28,000 acres of wetlands and some adjacent uplands which provides interconnected habitats for mammals, birds, turtles, frogs, and insects to move freely between land and water. This is especially important for many animals during certain life stages like breeding, rearing young or overwintering. The Ramsar site is high in biological diversity with more than 800 plants, 39 mammals, 140 birds, and 38 herptiles. There are many rare and threatened ecological communities, 44 rare plants, and 121 rare animals.

To gain insight into why the LWR is such an importance place, it helps to understand the topography and associated ecological plant and animal communities. There are 14 different ecological plant communities in the LWR. “Considered it as a landscape of ecotones separated by different plant and animal communities” explains Mike Mossman, retired DNR ecologist, “these ecotones are interconnected and allow plant and animal species to migrate or move with changes in water levels, climate and temperature”. Think of the river corridor in cross section as a series of topographical steps starting at the river as the lowest point, moving up to the sand bank, then beyond in the lower floodplain there are floodplain forests, sedge meadows, marshes, sloughs and oxbows lakes. Home to many frogs and turtles, and while one thinks of frogs as aquatic animals, all but the green frog and bullfrog spend most their lives on land but head for water to breed. Uncommon in other state floodplain forests, the threatened red shouldered hawk is common here and can be seen cruising in search of frogs and snakes for food. Intertwined in the floodplain but also found further up on the sand terrace one can expect to see dry-mesic prairie and oak barrens dotted with cactus. Home to the box turtle, six lined race runner, and the lark sparrow, which nests among cactus and has a beautiful song. Other herpes like the rare blandings turtle leave the wetlands and head for the barrens to nest. Next there are forested slopes, and sometimes exposed cliffs having a moist cliff plant community dripping with ferns and mosses. Finally, at the high point or bluffs there exists dry-mesic to dry prairie dotted with cactus, oak openings and pine relicts. Habitat not just for bald eagles but also rare birds like the acadian flycatcher, cerulean and Kentucky warblers.

Starhead Topminnow photo by nanfa.org

There are over a hundred sloughs and oxbo lakes that dot the landscape like a string of pearls within the LWR Ramsar site. Many have a high diversity of aquatic plants, insects and fish. These lakes harbor highly diverse floating leafed, emergent and submergent plant communities that support a plethora of wildlife. Plants like southern wild rice which feed birds, ducks and mammals. The showy spadderdock has a bright yellow bloom with a fiery red ring in the center, and while fish pick insects off the underside of the pad, insects feed off the nectar of the bloom. The “LWSR is one of the highest-quality large warm water river reaches remaining in the Midwestern U.S.”, so says John Lyons and Dave Marshall, retired DNR staff. There are 98 different fishes, including 8 rare fish such as the state threatened blue sucker or the tiny state endangered starhead topminnow with its green-glow starlike spots on the head and near the dorsal fin. There are more than 45 kinds of clams with ten that are state threatened or endangered. Mussel beds within the site support more than 1% of the world’s population of the federally endangered Higgins’ eye pearly mussel. The link between mussels and fish is strong, since mussels spend part of their life cycle attached to the gills of specific fish species.

Cerulean Warbler photo by Robert Royse.

The LWR Ramsar site is important for its cultural resources and “contains a rich tapestry of effigy mounds and places of anthropological importance”, according to Mark Cupp, Executive Director of the Lower Wisconsin State Riverway Board. The site contains eight effigy mound groups in the shape of animals, linear embankments or conical domes, and built by a culture named the Effigy Moundbuilders. A large bird mound is easily seen during leaf off, on the south side of highway 60 just west of Muscoda. The Ho-Chunk (formerly Winnebago) Nation trace their lineage back to these mound builders. “That the Mounds were formed in close proximity to waterways and wetlands indicates the strong tie of these areas in tribal culture”, According to Cupp, and “The Ho-chunk historically managed wetlands through fire and animal husbandry, and wetlands continue to play a critical role in their cultural heritage.” A short hike up Blackhawk Ridge, accessed along highway 78 near Sauk City, takes you to more mounds and an historical marker that describes the famous Battle of Wisconsin Heights, led by chief Black Hawk.

Bluff Woodland Savanna photo by Mike Mossman

This designation is not just a feather in the cap for people from the great state of Wisconsin, it is much more. It promotes the identity of cities and villages along the river as an attractive place to live and where outdoor recreational opportunities are endless. It draws tourists, which in turn is a boon to local economies, especially during these times when local businesses are struggling as a result of the pandemic.

Recreation at the Lower Wisconsin River. Photo by Jean Unmuth.

Avoca Lake is in the floodplain of the Lower Wisconsin River. Photo by Jean Unmuth.

The LWR is a precious resource that is not without its problems both in terms of plant communities and water issues that negatively impact human and wildlife communities. With the invasion of the emerald ash borer beetle, we stand to lose many ash trees, a dominant tree in the site. A more open tree canopy will invite invasive plants that compete with native plants. Scientists documented high nitrates in the backwaters which negatively impacts aquatic animal life, promotes excessive beds of green algae, and shades out native plants that a complex food web depends on for specific life stages, food, nesting and rearing. Higher nitrates from agricultural and lawn fertilizer sources have been documented in our ground or drinking water, impacting human health.

Photo of a Spadderdock

The riverway has many public access points that invite those who like outdoor recreation or to simply enjoy the scenic beauty of blufftops that fall away to reveal hidden valleys and flowing streams. It is a quiet place to retreat, explore and breathe fresh air. Where one can observe red and yellow leaves spinning quietly over amber waters or watch sandhill cranes as they parachute through silvery morning mist, landing in dewy sedge meadows. It is a place of peace and hope, and heaven knows with the challenges of the pandemic and the upcoming election, we all need that these days.

For more in-depth information about the Lower Wisconsin Riverway Ramsar site, visit the following websites: wisconsinwetlands.org or ramsar.org

About the author

Jean Unmuth chaired the LWR Ramsar nomination committee and is a member of hte Lowery Creek Watershed Initiative. She monitors water quality in Lowery Creek as well as Little Bear Creek. She is a member of Wisconsin Wetlands Association, Friends of the Lower Wisconsin Riverway science team, and has 30 years of experience in water quality and fisheries with the Wisconsin DNR.

Read more about why Frank Lloyd Wright loved Wisconsin and its unforgettable natural splendor in his essay, “Why I Love Wisconsin.”