Willey House Stories Part 8 – A Rug Plan

Steve Sikora | Sep 18, 2018

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

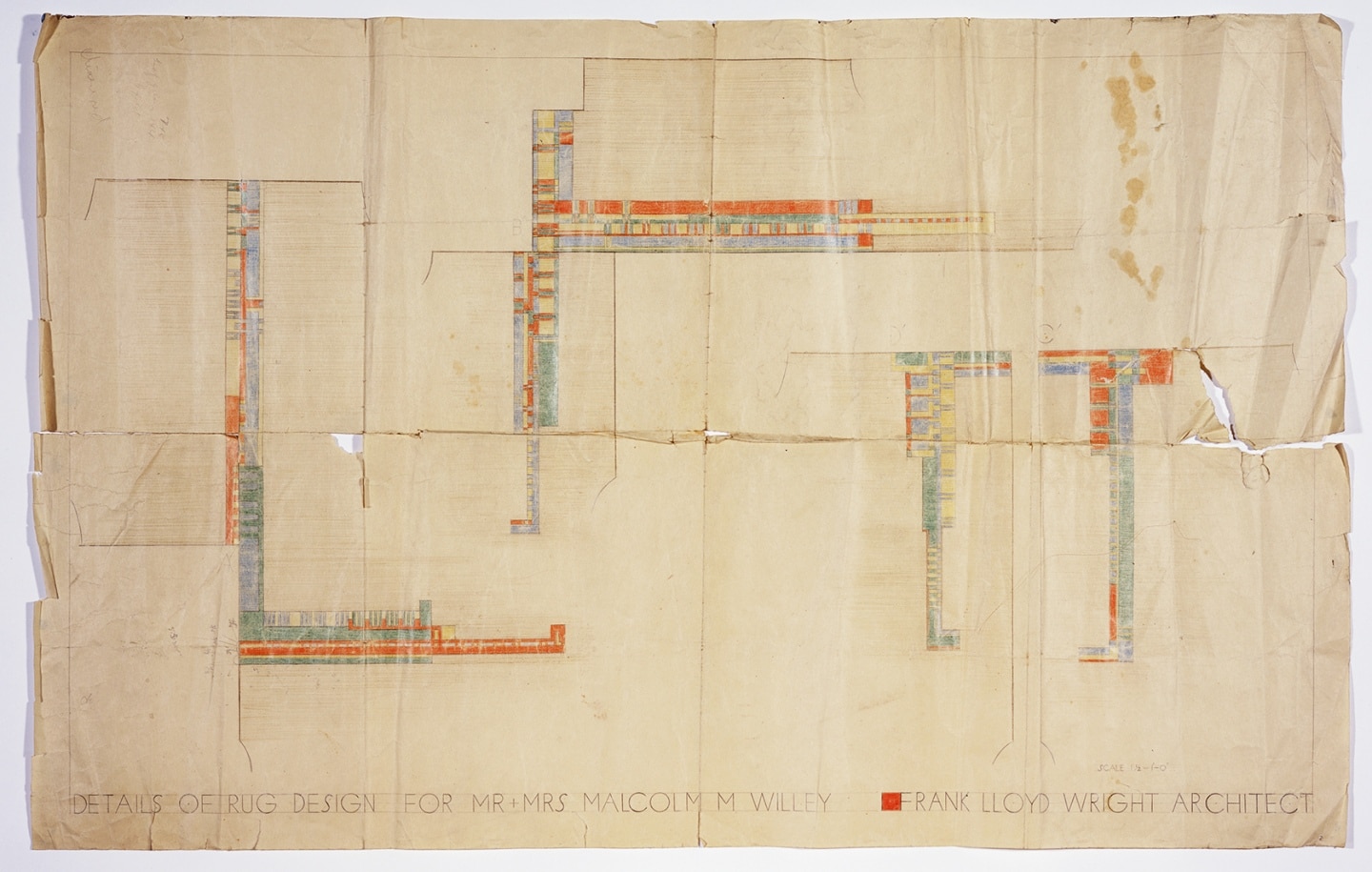

A number of restoration attempts preceded ours at the Willey House. One such aggregation that coalesced during the 30-year ownership of Harvey Glanzer, called themselves, “Team Willey.” Two dedicated, former members, John Clouse of Twin Cities Public Television and Karen Duncan of the University of Minnesota’s Frederick Weisman Museum, visited with a large flat file shortly after we acquired the house. They knocked at the kitchen door. Members of the former Team Willey invariably came to the kitchen door, because the main entry door—damaged during a forced entry—had been screwed shut for the duration of Team Willey restoration efforts. On this day, they brought with them a file box of artifacts, belonging to Russell and Jane Burris, the second owners of the house. It contained resources of significant historical value. In the box, among other things was a tattered and folded, color pencil rendering of pattern elements. The patterns constituted an overall rug motif, created by Wright for floor coverings at the Willey House. The rendering consisted of four elongate, multi-colored, geometric shapes. They projected in different directions and were labeled A through D. Beautiful as this drawing was, it offered no indication how the parts related to the spaces in the house. On loan to us for several weeks, we photographed and copied the designs before returning the box, which resided for the moment, at the Frederick Weisman Museum, on the University of Minnesota West Bank Campus.

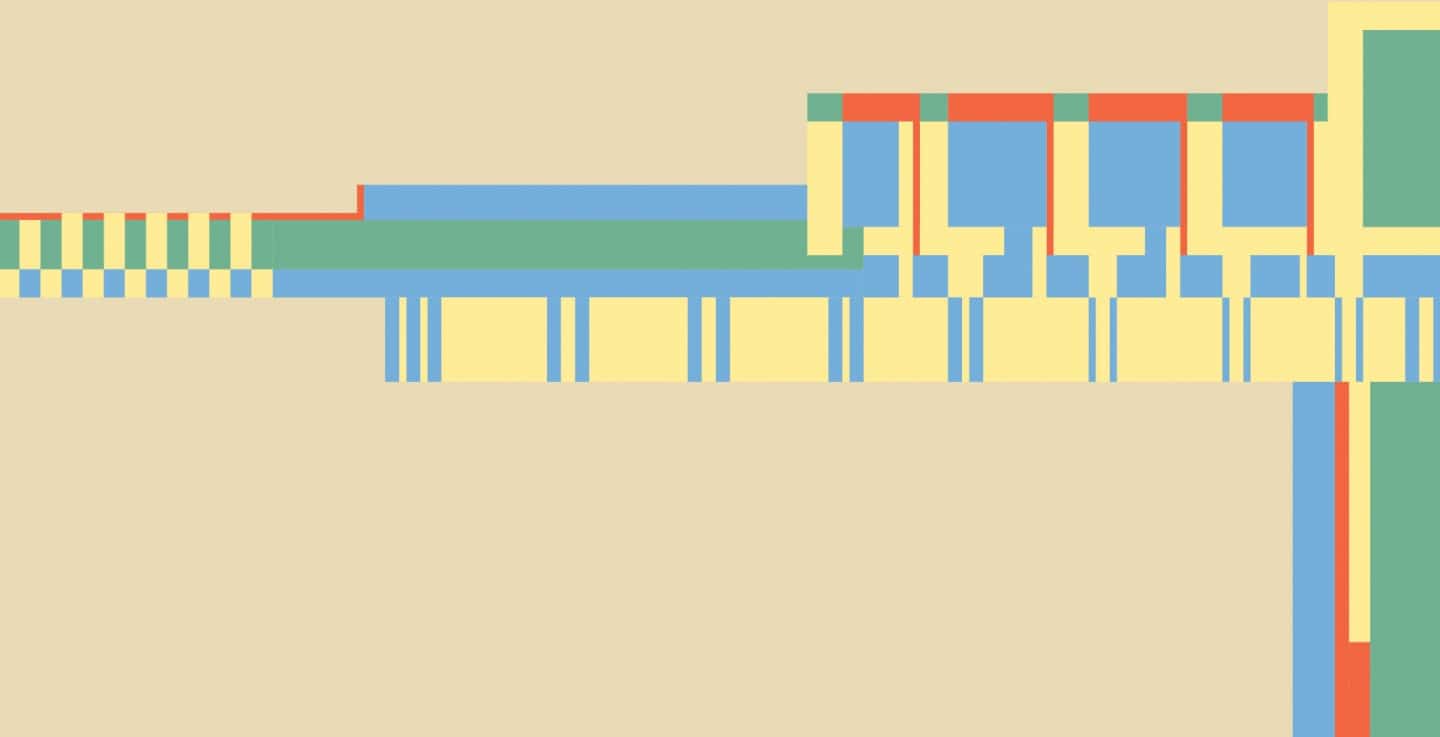

To make these patterns useful required digitizing them. A particularly detail-oriented designer in our office was assigned the task of replicating the layout to scale in Adobe Illustrator, a digital drawing program. The original rendering was delineated in lead pencil, the solid fields filled with colored pencil. The medium used was an ordinary, buff-color drawing paper, its dimensions: 35 3/8”W x 22”H. The highly detailed drawing consisted of rhythmic, linear forms overlaying a paper-colored background. The slightly muted palette of red, blue and green and yellow, geometric designs was easy to interpret but the background was undefined. Equally unclear was exactly how these patterns were to be adapted for use as a rug, or series of rugs in the Willey House. Nevertheless, they were recorded and saved for future use as the restoration proceeded.

Willey House rug plan detail sheet, color pencil. Courtesy of the Willey House Archives.

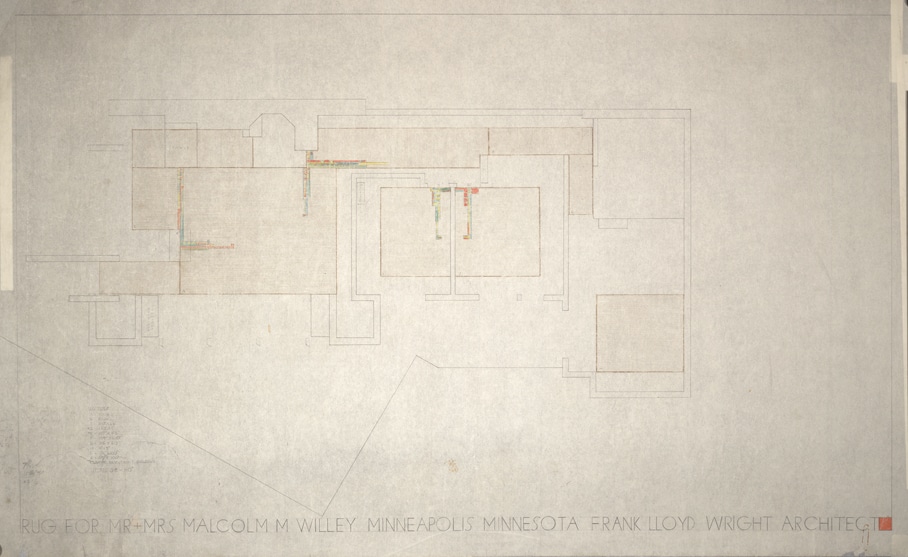

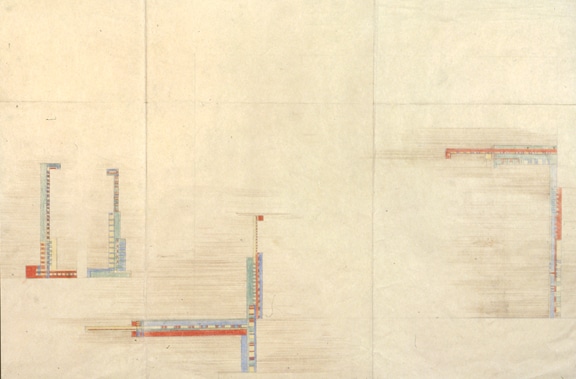

A year or so later, my research took me to the Wisconsin Historical Society, where a portion of the collection, of the late John Howe’s drawings and photographs had recently been donated by his wife, Lu. My hope was that it contained missing furniture designs that might be included in the plan set, and I wasn’t disappointed. In it I discovered a trove of drawings labeled Willey House, well over 50 of them. At least 26 were unrepresented in the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives. An equal number appeared to be copies of drawings then housed at Taliesin West. Included in that collection of Howe drawings was the Rosetta Stone, a floor plan of the Willey House with the rug designs superimposed. It was a key to the placement of the elements from the rug plan in the Burris’ box!

Key to Willey House rug plan. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

The collected correspondence between Nancy Willey and Wright, shed considerable light on the rug plan. Just prior to moving into their new home, Nancy Willey inquired, “It’s probably hard to advise about the house without seeing it, but if, as and when the Willeys have money, what kind of rugs does Mr. Wright suggest? I think I could sell our orientals tho at a loss … Does Mr. Wright think a cheap monotone rug better than good orientals?”

In response, Gene Masselink asked, “And what have you in the way of rugs?” There is no record of an answer from Nancy other than a celebratory telegram sent in November of 1934, that the Willeys had moved in.

Fifteen months later, in a letter dated February 12th, 1936, sent from La Hacienda in Chandler, Arizona, Eugene Masselink wrote, “Mr. Wright has worked out your rug plan completely. The drawings are now being completed and will be sent out to you as soon as Mr. Wright approves them on his return from Chicago within the week.”

Built on the former polo grounds of the San Marcos Hotel in Chandler, AZ, La Hacienda, a small 24-guest room establishment, became base of operations for the Fellowship during the winters of 1935 and 36, the years prior to the creation of Taliesin in the Desert. It was at La Hacienda that the Broadacre City model was constructed.

Five days later, he posted another letter, “Mr. Wright has returned from Chicago and the rug plans and designs will be sent out ‘as soon as possible’ – and you know better than many people how soon that can be.

Hearing and reading about the snow and cold up north – we’re wondering how ‘THE SECOND WINTER IN THE WILLEY HOUSE’ is progressing.”

On February 25th Gene wrote, “Mr. Wright has decided that the color of your rugs should be a light Cherokee red Klearflax [Klearflax Linen Looms Company, Duluth, Minnesota].

The sizes and patterns have been sent to you. These patterns are to be stitched into the Klearflax with heavy colored waxed linen thread.

Send a sample of the Cherokee color for approval.”

In reply, on March 9th Nancy wrote, “The rug designs were received with delight by us. I have written to the Klearflax Co. If they have no representative who can be interviewed in Minneapolis, I will go up to Duluth a little later in the spring. I will report progress.”

Nancy visited the Klearflax Rug Co in Duluth as recommended by Gene, and on March 26th Nancy communicated to Wright, “Thank you for the rug designs, they are beautiful, I’m a little confused by my first interview with Klearflax representative but it will undoubtedly come clear in due time. Will you ask Gene to send us a sample of your Cherokee red. There is no such color in the rug catalogues. [But there soon will be! An account of the history of Cherokee Red will be addressed in a near future Willey House Stories 11.]

They told me the design would have to be tufted into the wool by hand. I think this might be satisfactory. Your suggestion of stitched with heavy waxed linen thread met with the familiar ‘can’t’ – [Is it can’t?]

I believe there is no possibility of a discount. Those fellows have their price holding agreements with their dealers and hold tight. [And fight the closed shop…the hypocrites!]

I have just heard of rugs made on a rubberized back, so that the designs may be cut out and the desired colors just slipped back in like a jig-saw puzzle.”

Nancy sent her greetings to Olgivanna “especially” and asked that they stop by on their way back to Wisconsin.

On March 31st, Gene responded with a source for the Cherokee red color and followed with, “We have, also, just gotten in touch with the ‘rubberized-back’ rug people in connection with another house. Mr. Wright says that this could be used for your design. The company with whom we’ve corresponded is the Bigelow-Sanford Carpet Co., 140 Madison Avenue, New York. But they will quote prices only through local dealers. Undoubtedly there will be a dealer in Minneapolis. ‘Lokweave’ is what they call this particular brand of their product.

Arizona has been a great experience this winter. Better even than last year. We are starting home in a day or two – afraid Minneapolis is not included in the itinerary. Maybe a special trip later on!”

Willey House rug plan detail. Courtesy of the Willey House Archives.

Conversations on the subject of the rug plan end there, leaving us uncertain why a rug was never woven. Quite possibly, cost was an obstacle. It is not until January 4, 1938 that the rug design is again a subject of conversation. Nancy wrote to Gene, “I have already started (at last) having fun with the house. During the holidays I got some monk’s cloth and worked the rug designs into it in yarn, hung them in the bedroom as curtains, and surprised Mr. Willey with them when he came home from his trip East. They are simply beautiful and SO gay! I don’t know why I waited so long to do something so pleasant. Please tell Mrs. Wright I think her painting ‘lesson’ gave me the courage to start.”

To date we have found no photo evidence of the curtains Nancy made from the rug designs.

In a later life interview, Nancy admits that she “lost the rug plan.” In her 1995 Frank Lloyd Wright Oral History interview she notes that Gene rendered the design. “He did the rug, which I lost. And I put them into curtains for the bedroom. They were monk’s cloth, and I wove with yarn this design. And I think it was Gene’s design.” Fortunately, the rug detail sheet did survive, though somewhat worse for wear. Folded into eight panels and creased to the point of perforation, the color pencil rendering remains sharp and crisp. The rug design is scaled on the order of the enormous geometrics done for the Taliesin living room and the David Wright House both designed in the 1950s. It is reminiscent of both Barnsdall and Bogk House rug patterns, but more visually active and completely asymmetrical.

The rug design along with a number of other treasures were generously donated to the Willey House archive by the Burris family after the death of their parents, a bequest for which we will be eternally grateful, in that made so much of the research for the restoration and ongoing study possible. It still does!

Sketch of design elements of Willey House rug plan. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives.

Which brings us to why we, the current owners, have not proceeded with execution of the rug plan, now entirely in our grasp.

To be honest, it would be breathtaking to see the rug plan in place. It would be a dynamic change and utterly transformative to the interior of the house. However, our reservation is this – one of the unique features of the Willey House is Wright’s monolithic use of red brick on the interior and exterior walls, terrace, steps, fireplace and particularly the floors, which extend seamlessly from indoors to outdoors. To cover the bricks, which the rug plan does, would be to obscure this marvelous aspect of the house, and we can’t bear to do it.

What about the original resources? Founded in 1909, Minnesota’s once prominent Klearflax Rug Co. no longer exists. The business was shuttered in 1953. Klearflax described their product as “A beautiful, thick, heavy, reversible, long-wearing floor covering made entirely of pure flax linen. This linen (flax) is the sturdiest of all textile fibers.” Klearflax earned its place in private homes through long service in public buildings. A Klearflax rug was placed in the main entry of the New York Waldorf Astoria Hotel. They were used in the cottages of the Grove Park Inn, Ashville, NC. Another example, made in 1939 and weighing a half-ton, at 15 feet by 30 feet, was woven for the Finnish capital in Helsinki. Wright specified a Klearflax rug for the 1939 Pope House.

The alternative manufacturer, The Bigelow-Sanford Carpet Co. Inc. of Amsterdam, NY, listed in Sweet’s Architectural Catalogues, 1933, reads, “Since 1825 – Weavers of Carpets and Rugs to Contract Specifications and for the Home / Main sales office 136 Madison Avenue, New York, N. Y. The service offered you by Bigelow-Sanford’s Contract Department is complete. Starting from the time when a building is in the blue-print stage, it follows through to the laying of carpets or rugs on the floors. This comprehensive service to architects, builders and decorators is yours to call upon. You may use it in whole or in part. Get in touch with any of the above branches whose personnel is trained to work with architects and builders on all carpeting questions” was, at the time, the largest carpet manufacturer in the world, closed in 1964.

Unfortunately, the original rug manufacturers, methods and materials are now lost to history. A suitable, alternative source will need to be identified to move forward. Perhaps then, sometime in the future, “when money rolls uphill” to quote Nancy Willey, a section or two will be woven, so we can gain the full impact of Wright’s vision for the Willeys.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers

Part 7: Step Right Up