Willey House Stories Part 16 – A Red By Any Other Name

Steve Sikora | Sep 23, 2019

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

I suppose you could say that any avenue of serious inquiry never comes to an end. Reading Willey House Stories Part 11 – Origins of Wright’s Cherokee Red should be a prerequisite to this installment, but since I can’t enforce compliance with that precondition, I will instead issue this spoiler alert: The story traces the history of Cherokee Red and cites the first time Frank Lloyd Wright specified it as a color. In a letter from Wright’s clerk-in-the-works, Gene Masselink, he mentioned that Wright first “saw” the color on a trip to the coast.

At the time of writing Part 11, I made a leap of faith judgment that Gene meant the West Coast and that the color seen was the particular red used in the palettes of Pacific Northwest tribal artworks. Sure enough, after the blog went live I found in the appendix of David De Long’s book, Frank Lloyd Wright: Designs for an American Landscape 1922-1933 a calendar showing Wright had indeed been in the Pacific Northwest in March of 1931, delivering lectures at both the University of Oregon, Eugene and University of Washington, Seattle. Feeling especially proud of myself, it seemed to confirm what I suspected Wright’s original conscious inspiration for Cherokee Red to be. There is more to the account, but you’ll need to read it for yourself in Willey House Stories Part 11.

Amelia Earhart in the 1935 Ford Indianapolis 500 Pace Car with phaeton top. Credit: Vintage Ford Motor Company Public Relations.

That said, I recently stumbled upon a Depression-era gossip column from Madison’s own Wisconsin State Journal. In it, columnist and personal friend of the Wrights, Betty Cass— who was apparently quite familiar with, and most anxious to report upon the goings on at Taliesin— wrote:

August 9, 1935 – Madison Day by Day, by Betty Cass

Wherever they go, the color of those two Fords belonging to the Frank Lloyd Wrights, the convertible coupe of Mr. Wright’s and the sedan-touring car of Mrs. Wright’s, always attract much attention.

No one has ever seen Fords (or any other car) of that color before. It is a luscious brick-reddish-burnt-orange, if you know what I mean. The Wrights call it “Cherokee red” for some reason or other: maybe because they got the cars just before they went to Arizona last winter. I called it “Ripe persimmon” when I wrote of them the other day. And it’s been tagged, either mentally or orally, at least a dozen other shades by people who see them.

But the point of this story is not “What color is it?” but “WHERE and HOW did they get them that color?” And the answer:

When the Wrights started to get their new cars last winter they decided to have them painted some unusual color…something which would be artistic and different from other cars and which would, at the same time, express some of the personality of Taliesin … but WHAT color?

They discussed this shade and that one but couldn’t decide on exactly what they wanted until one day at a meal Mr. Wright noticed a beautiful Catalina pottery cream pitcher of a luscious, rich, brick-reddish-burnt-orange shade.

“There! That’s the color of the car” he exclaimed. And Mrs. Wright agreed that it certainly was a gorgeous color –But how to get the Ford Company way over in Detroit to paint two cars the same shade as a cream pitcher at Taliesin Wisconsin?

It didn’t take Mr. Wright long to figure that one out, however.

“Send them the cream pitcher and ask them to match it,” he said, and the cream pitcher was duly and forthwith packed and sent to the Ford Company. And in the required length of time back came the cream pitcher and two Fords to exactly match.

The Madison Day-by-Day column denoted the first of the Taliesin Fellowship’s annual winter pilgrimages to Arizona. Though Taliesin West or “the desert camp” as it was initially called, would not be founded for another two years, “a caravan of ten gray and red cars lead by a new V8 truck, painted red,” journeyed southwest, from Spring Green to La Hacienda in Chandler, Arizona to work on the Broadacre City model in mid-January 1935, as recounted to Nancy Willey by Gene Masselink. In his January 17 letter, he used only the simple color name “red” to describe the manner in which the vehicles were painted. Now we have a clearer picture as to the nature of that red.

Betty Cass’ anecdote about the cream pitcher was another thing altogether. After all it was Henry Ford who wrote, “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black.”

Though times had certainly changed since he made that statement and car sales were lagging during the Depression, sending dinnerware for a custom paint match ran contrary to the principles of mass production and was most likely a practice discouraged by the Ford Motor Company.

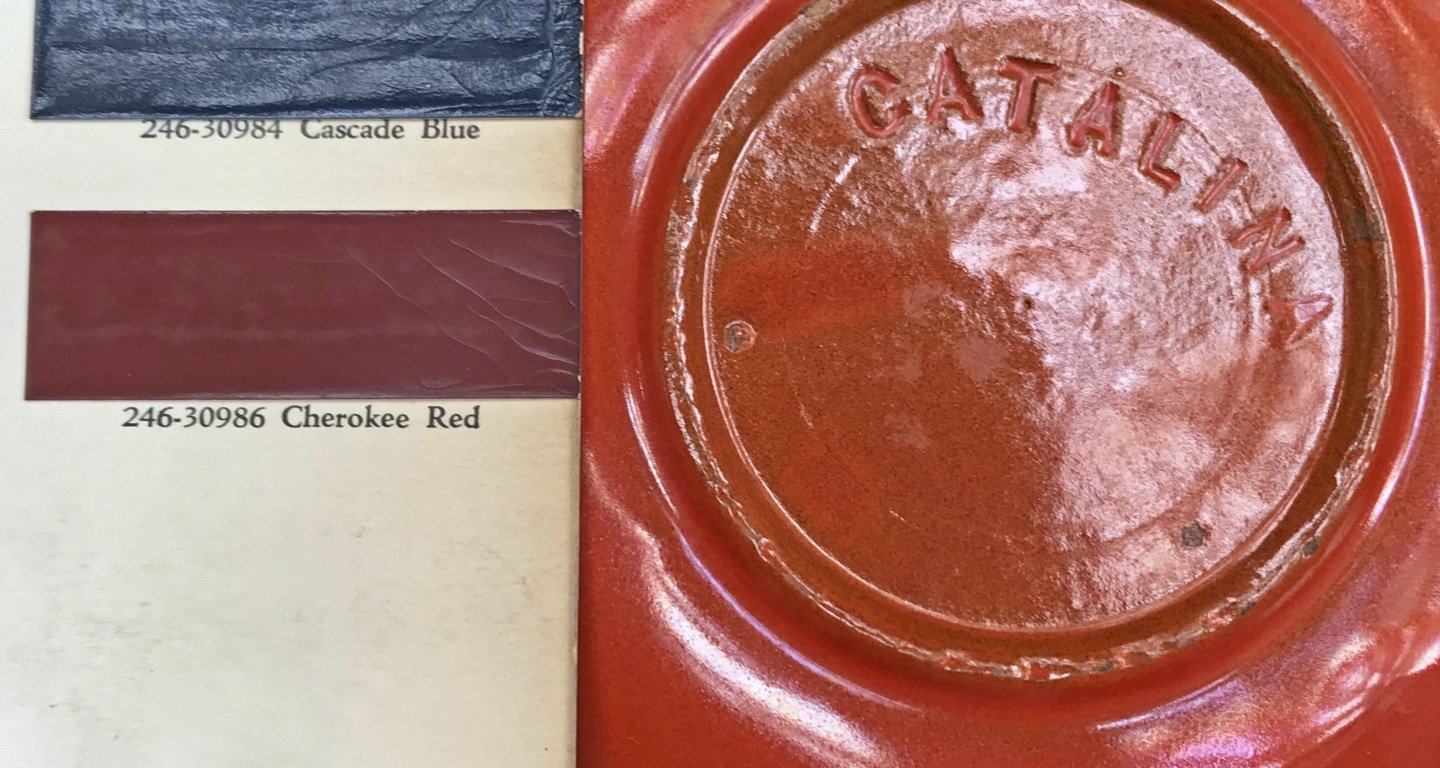

The request would have been all the more awkward to fulfill if that special match were some sensational hue, since the colors of the day were as bleak as the national mood. Still, Wright was a celebrity and perhaps they’d make an exception for the publicity value. My initial skepticism gave way to curiosity after a nagging conscience insisted I look further into Catalina Island Pottery. That’s when I saw that red glaze.

Catalina Island Pottery saucers in Toyon Red. (Pictured left to right) White clay body lighter end of scale. White clay body darker end of scale. Early redware clay body. Credit: Steve Sikora

The history of modern ceramics on Catalina Island began with the discovery of clay and mineral oxide deposits while fresh water wells were being drilled in the teens. The company began by producing commercial ceramic tile and pipe to satisfy the current trend in Spanish Revival-style architecture. The earliest retail pottery pieces produced by the company were fashioned as souvenirs for visitors to the island. These decorative items were made starting in 1927. By 1928, glazes were introduced and in that same year ceramicists from Pacific Pottery in Los Angeles were recruited as the company soon found a niche in the manufacture of ceramic tableware. With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 Catalina tileworks, as it was still called, scaled back on knick-knacks and refocused solely on the making of color-glazed dinnerware. Their distinctive glazes were given evocative names such as Catalina Blue, Descanso Green, Monterey Brown, Manchu Yellow, and Toyon Red. Vivid Catalina dinnerware predated Fiestaware with its flamboyant use of brilliant hued glazes. Toyon Red is the color of the cream pitcher that Betty Cass was referring to, named for Toyon Bay, a geographical feature of the island.

Catalina Island Pottery saucers in Toyon Red. (Pictured left to right) White clay body lighter end of scale. White clay body darker end of scale. Early redware clay body. Credit: Steve Sikora

Catalina Pottery was famous for its indigenous redware clay and glazes all sourced on the island. Red clays were the ideal medium for commercial, architectural products but less desirable for dinnerware. So in order to compete effectively in the marketplace, in November 1933 the company began importing white clay from mines owned by the Pacific Clay Company in Lincoln, California. This particular clay deposit, known as the Ione formation, is located in an area outside of Sacramento on the western side of the Sierra range. Coincidently, clays from the Ione deposit will figure in many other connections to Wright in the decades to come. Stay tuned.

Toyon Red varied significantly in hue from piece to piece. Dinnerware made as late as 1933 still used the red clay bodies native to the island. The dark under-layer of a redware clay body naturally resulted in a deeper red glaze. It is likely that by the time Wright encountered Catalina Pottery, the company had already converted production to white clay. Only the white clay body allowed the Toyon Red glaze to approach a brightness factor that Betty Cass would be compelled to name “ripe persimmon.” In any case, the color range of Toyon Red resembles the spread we see elsewhere in the shade Wright called Cherokee Red, which is to say a broad tonal spectrum of orange to red-brown color resulting from the use of iron oxide pigments in the glaze.

If the Ford story is true there should be some evidence of it. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives hold one piece of correspondence from Wright to a representative of the Ford Motor Company. The database of Wright correspondence assigns the date of this letter as May 1, 1933, but the document itself is an undated and unsigned carbon copy.

My dear Simons

Milwaukee Branch Ford Motor Co

My dear Sir:

I have asked Mr. John Schoenmen to get me a Ford touring sedan: the model with trunk extension built into back part of the body – but instead of stationary top I desire this model completed with a convertible sedan phaeton top.

I have seen this combination on the street in Phoenix and Los Angeles and liked it. Each time I saw the car it was a color I liked: A color not listed as either a Standard Ford or a Special Ford color I now find.

I do not care for the convertible touring car with the sloping non-extended back such as I saw in a Chicago showroom as Standard nor do I care for the regular line of Ford colors.

The color I want would be known to the decorator as “Sanguine,” a fairly dark russet or reddish brown.

Can you send Mr. Schoenman a color card in which this color might be found a find out if the combination of convertible top and built in trunk-extension behind can be had from the factory and if so, when delivery could be made.

Sincerely yours,

(unsigned)

In comparing the differences between Fords manufactured during the 1933-1936 model years, the vehicle Wright describes in his letter did not exist in 1933. However, a bumped out “integral trunk” feature did re-appear as an option in 1935, after an absence of several years.

The configuration requested by Wright was a 1935 Model 48 Convertible Sedan with a trunkback, sometimes called a humpback. This is an unusual configuration. I was only able to find one photo of a Ford configured this way, and that was a 1936 model. If the date on the letter from Wright was placed one year later, into a 1934 timeline, it fits nicely with the newspaper column written by Betty Cass.

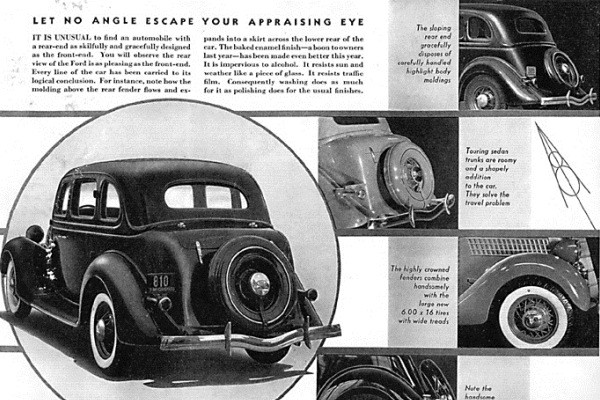

1935 sales brochure showing the trunkback feature. Credit: Vintage Ford Motor Company Public Relations

Unlike today, a vehicle model year did not appear in showrooms until January of that calendar year or late in the preceding year, in other words a model year 1935 car may have been marketed in late 1934, but not available for sale until 1935. During the Depression a person of Wright’s celebrity status could possibly have had his new cars paint-matched to a piece of pottery or a decorator color he called out. It is also possible that Mr. Simons or someone else at Ford Motor Company made Wright aware of the Olds Motor Works 1935 color palette, which would have been concurrent with his request.

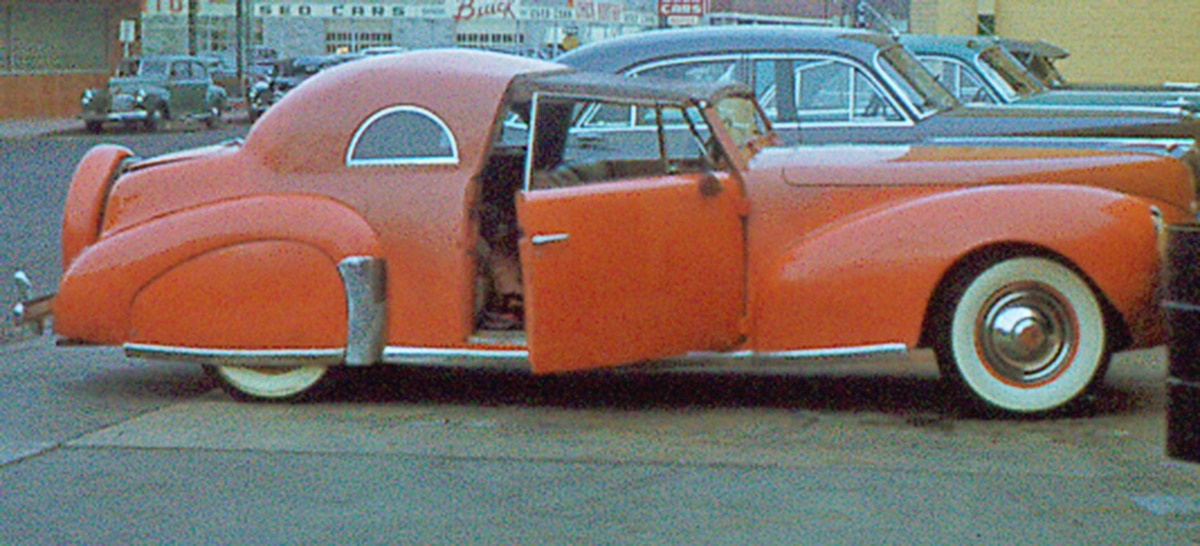

1936 Ford Model 48 with the unusual configuration of convertible top and “trunkback,” the same features as requested by Frank Lloyd Wright. Credit: Vintage Ford Motor Company Public Relations

The 1935 model year is the one and only year featuring the color named Cherokee Red. Though the color on the Old’s paint chart is darker in tone than Toyon Red it is the only source for the name Cherokee Red.

So we have some new antecedents to Wright’s Cherokee Red to add to our vocabulary, Toyon Red, Ripe Persimmon, Dark Russet, and my new personal favorite, Sanguine. Sanguine took me back to college life drawing class, and the crisp lines made by the hard sanguine crayons we used when not making awkward figure studies, smearing charcoal onto toothy newsprint.

Betty Cass’ luscious description of the color as “Ripe persimmon,” along with Wright’s own description of the color as “Sanguine,” points to the white clay bodied samples of Toyon Red from Catalina Pottery as a probable precursor. I do believe the color he initially requested from Ford was a lighter shade of Cherokee Red. See the photos of Wright’s 1940 Lincoln or Wes Peters’ 1955 Mercedes 300SL Gullwing as examples. These paint jobs definitely skew to the lighter and more orange end of the Cherokee Red spectrum. And to reiterate, in Gene Masselink’s letter to Nancy Willey, he said that Wright intended a lighter value than that shown in the Old’s paint swatch.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s customized 1940 Lincoln painted in a version of Cherokee Red. Credit: Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives

March 31, 1936 – “Dear Mrs. Willey: CHEROKEE RED is an “Indian” Red. It is the color all Taliesin’s Fords are painted. Mr. Wright saw it out on the coast last winter and we finally discovered it as one of Oldsmobile’s standard Duco colors. Mr. Wright says that this should give you the general tone-the value should be lighter. The color of the cars has faded and is more what Mr. Wright means to be used.”

So Wright’s signature color could have been called Toyon Red, but the name that stuck, is the one cited to Nancy Willey, one of just seven somber colors in a 1935 Olds Motor Works color chart. It is still the first client specification, a suggested background for the Willey House rug plan, and one executed soon after for the metalwork at Fallingwater.

As I stated in the introduction to Willey House Stories 11, “There are many Cherokee Reds.” The inspiration for the color of the Wright’s 1935 Fords may well have come from a Catalina Island Pottery cream pitcher on the breakfast table at Taliesin, but orange-tinged as it was, the name given to Wright’s new color preference was still Cherokee Red, a name that could come only from the Olds Motor Works paint chart.

The 1955 Mercedes 300SL Gullwing belonging to Wes Peters painted in a Cherokee Red leaning to the orange end of the spectrum. Credit: Courtesy of Douglas M. Steiner, Edmonds, WA.

The 1935 Olds Motor Works Duco Paint chip for Cherokee Red against Catalina Island Pottery glaze Toyon Red (redware clay body, dark end of the spectrum). Credit: Steve Sikora

The ideal conclusion to this post is an account I just heard from Craig Jacobsen, who was a Taliesin docent. In 1984 or 1985 Wes Peters, who was always good for a story told him, “One day Gene (Masselink) was driving Mr. Wright around downtown Phoenix when they pulled up to a red light. Admiring the car in front of them, Mr. Wright asked Gene to go ask the driver what the color of the car was. Gene did as asked, saying to the driver that the architect Frank Lloyd Wright was in the car behind him and he wanted to know what the color of his car was called. When Gene returned to the car, Mr. Wright asked ‘What did he say?’ and Gene replied: ‘He said it’s a special edition 1935 Oldsmobile and the color is called Cherokee Red.'”

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers

Part 7: Step Right Up

Part 8: A Rug Plan

Part 9: Hucksters, Charlatans, and Petty Criminals

Part 10: Lo on the Horizon

Part 11: Origins of Wright’s Cherokee Red

Part 12: One Thousand Words

Part 13: The Plow that Broke the Plains

Part 14: Separated at Birth

Part 15: Trading Drama for Poetry