Willey House Stories: The Space Within: Part 3, “Sense of Shelter”

Steve Sikora | Mar 16, 2021

In this third segment of a special five-part feature series for the ongoing Willey House Stories, homeowner Steve Sikora explores variations on the theme from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation’s Spring 2021 Quarterly issue “The Space Within.” In Part 3, titled “Sense of Shelter,” Steve explores three concepts: 1. Neil Levine’s Concentric Triangles, 2. Venn Diagram, and 3. The Labyrinth.

The Space Within – Part 3: Sense of Shelter

“There is a well-balanced interpenetration (that is to say, sense of proportion) of the sense of shelter …”

—Frank Lloyd Wright, The Natural House

All diagram renderings in this essay by Sara Sparrow.

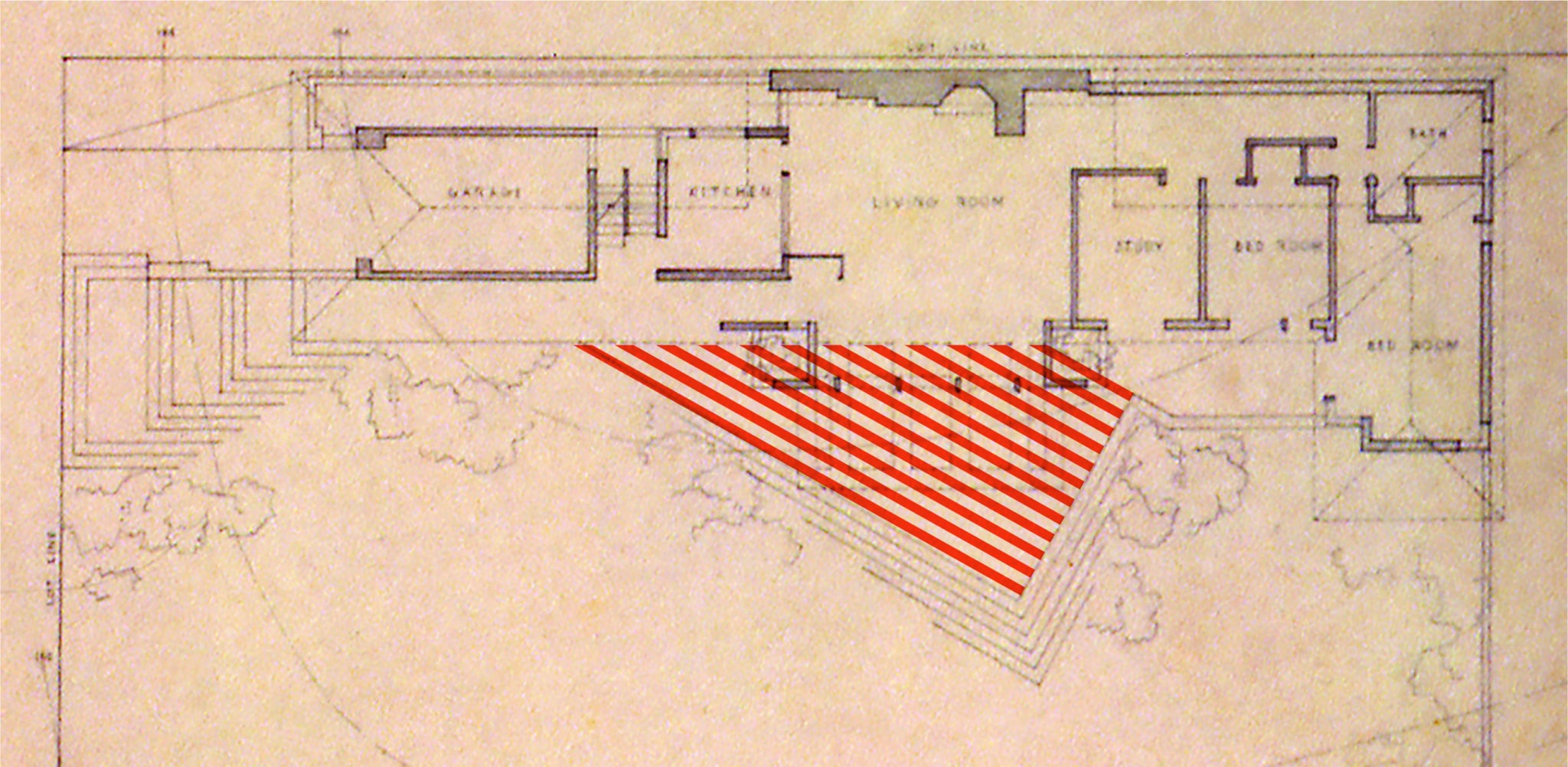

Concentric Triangles

Why would Wright apply a triangular terrace to what seems to be an otherwise rectilinear house? Architectural historian Neil Levine had an insightful answer. He noted that there are a number of diagonal axes in the rectilinear, scheme 2 plan for the Willey House.“ In an essay on Wright’s use of Diagonal Planning, in On and By Frank Lloyd Wright: A Primer of Architectural Principles, a book of essays edited by Robert McCarter, Neil Levine made some fascinating observations on the geometry of the Willey House.

From the street, a series of steps, decreasing in width at an angle of thirty degrees into a triangular terrace carrying the eye out to the end of a brick wall at the eastern edge of the lot. From the entrance to the living room, a diagonal axis carries the eye straight to the corner fireplace. The view through the passage to the bedrooms is at an angle of thirty degrees, literally mirroring the view along the edge of the outside terrace. The opposing diagonal, defined by the projecting pier of the fireplace, parallels the thirty/sixty-degree angle of the terrace, thus skewing the space of the room toward the southwest. As you turn around in that direction, the terrace appears to swing out from under your feet as if hinged to the edge of the brick walk; and the diagonal vista it opens up extends the view far beyond the confines of both house and garden.

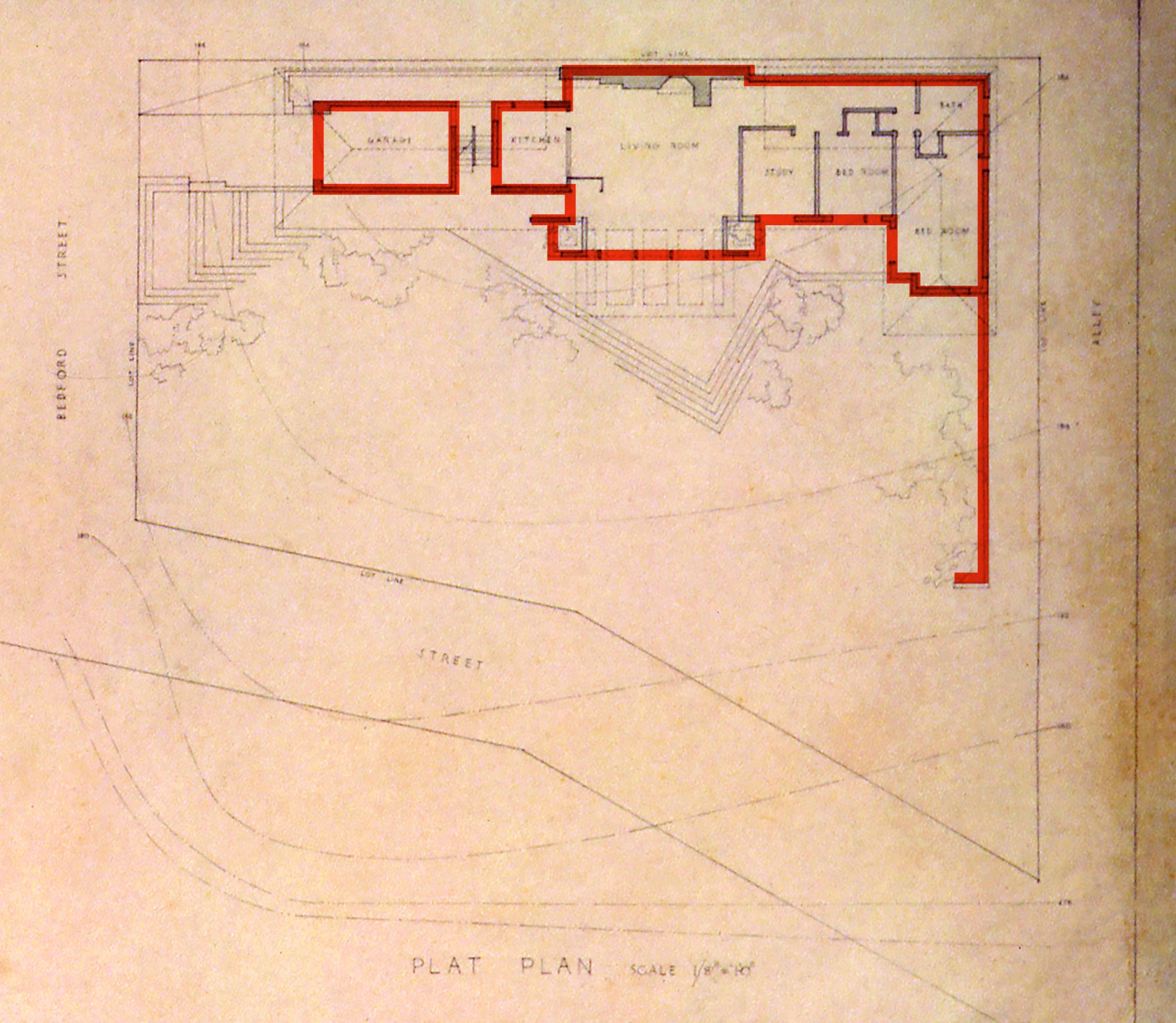

Fig A: Concentric Triangle, Willey House.

To prevent the space from becoming symmetrical, Wright introduced several diagonal axes into the plan of the living room. (Figure B) There is for example, a stepped wall that echoes the entry steps. It disrupts the expanse of otherwise flat north wall with a subtle shift in plane. Then, he introduced as extension to the fireplace a lighted, masonry pier. It thrusts forward from the hearth into the room, partially blocking the view down the gallery hall. (Figure C) When a line is drawn from one side of the hearth on the stepped wall to the other, at the end of the extended light mast, a more extreme angle is described. That diagonal line matches the diagonal of the outside terrace.

The terrace is a 30/60/90 triangle that penetrates the living room. The terrace bricks are laid at a 30-degree diagonal to those on the living room floor. In the place where the triangle enters the living room the bricks abruptly change direction.

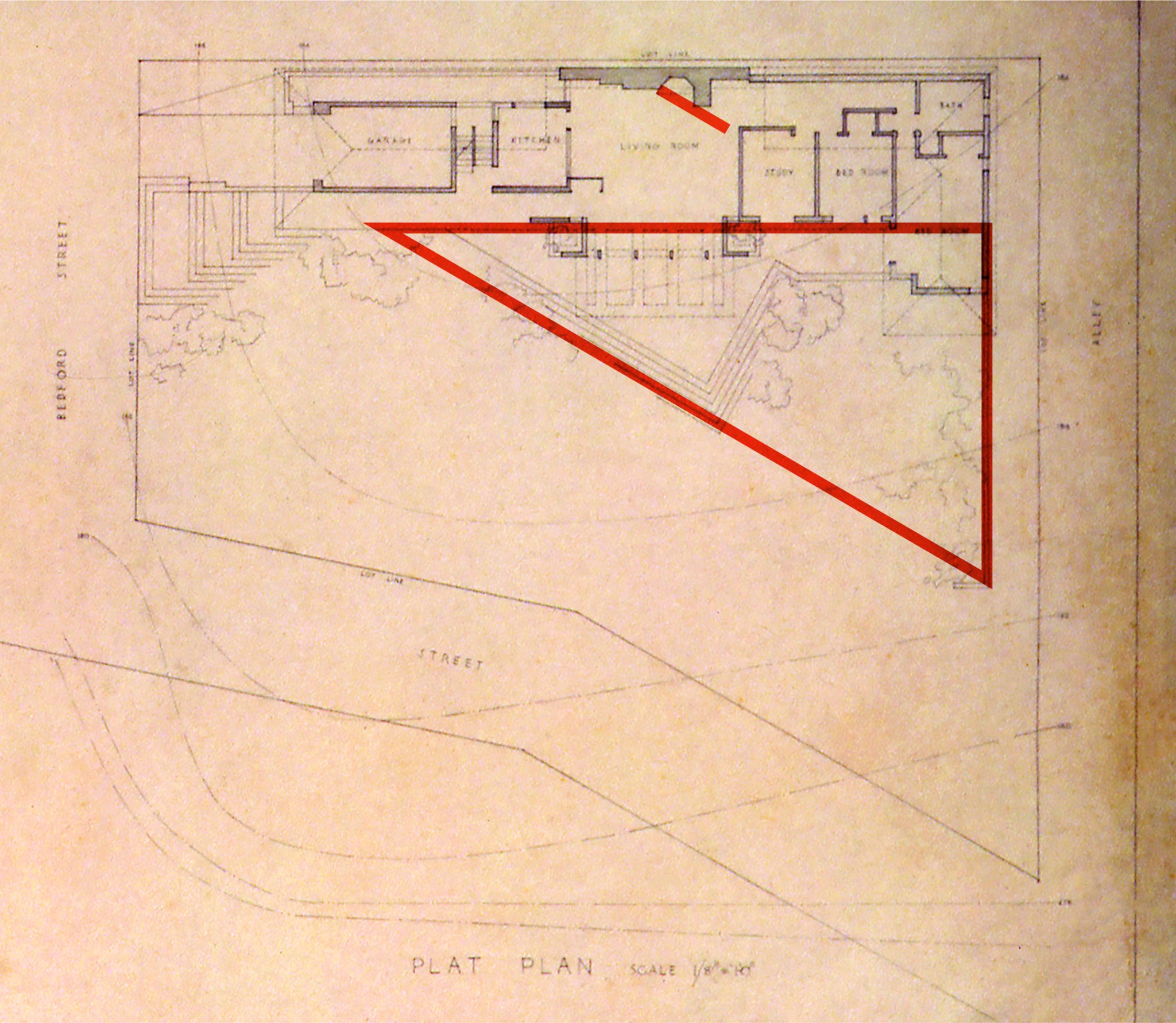

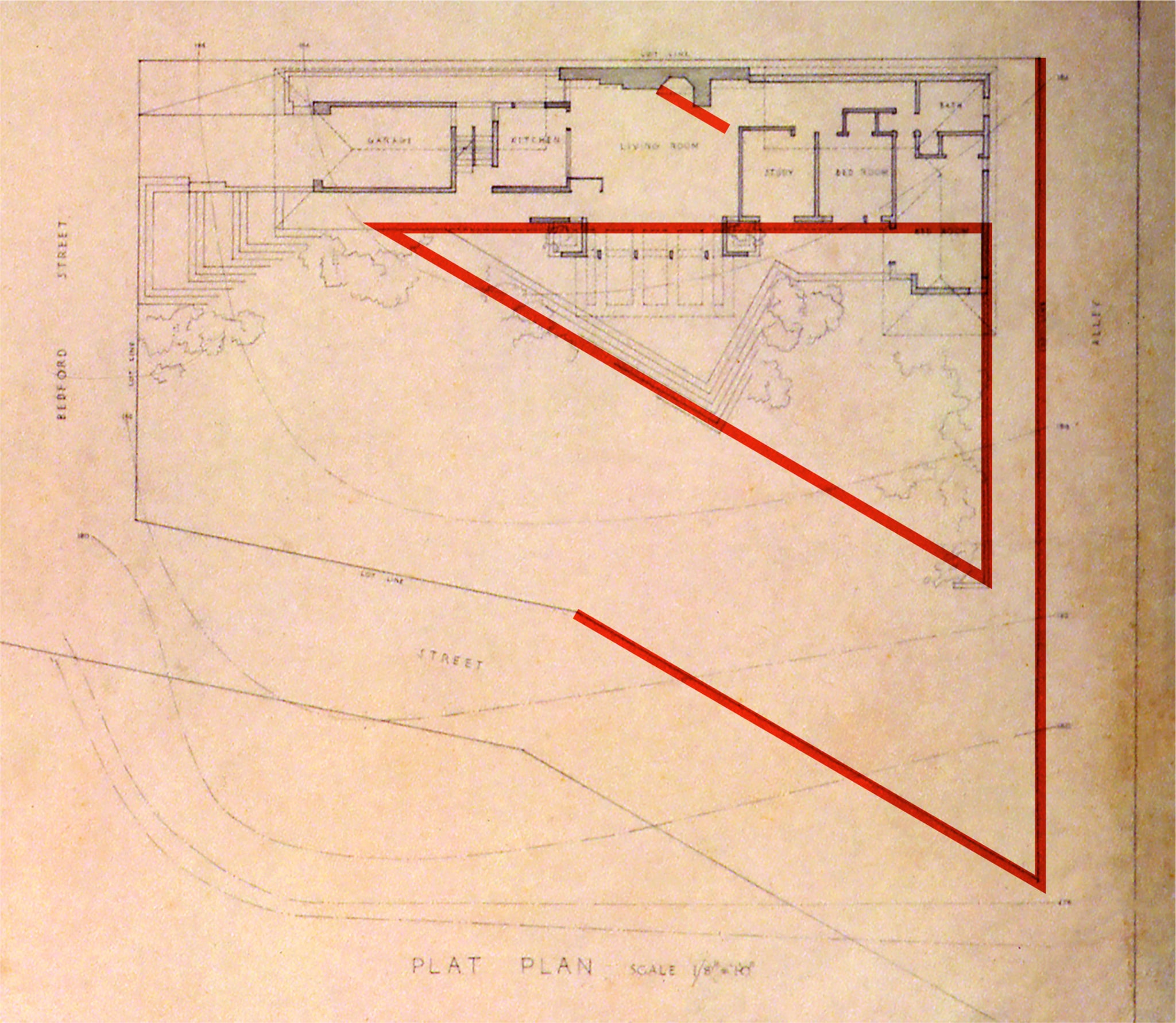

(Figure D) If one follows the outer line of the terrace steps they point directly to the end of the garden wall. (Figure E) When connected, this creates another, larger 30/60/90 triangle that shows how the terrace pulls the whole of the composition together. Wright worked from a plot plan when planning the house. Though property lines are no longer visible today, the lot itself was of irregular shape. (Figure F) A diagonal border of the lot matches the angle of the terrace and the hearth.

Fig. E, concentric triangles

Fig. F, concentric triangles

So Wright effectively takes what might seem like a random detail inside the house and couples it with the exterior terrace, fusing inside with out. He then goes a step further and links those design elements to the lot itself. Thus, an interior detail connects in and out, which ties the composition of the house together, then associates the whole to the ground plan itself. This is what he meant when suggesting that his houses grew “out of the ground into the light.” But there is still more. Neil Levine noted that the same angles that tie house to lot also match the meander of the Mississippi River to the south. So, subtle interior diagonals serve to lock the whole of the composition together, tie the house to ground, and ultimately bridge interior living space to the far horizon in a series of expanding, concentric triangles.

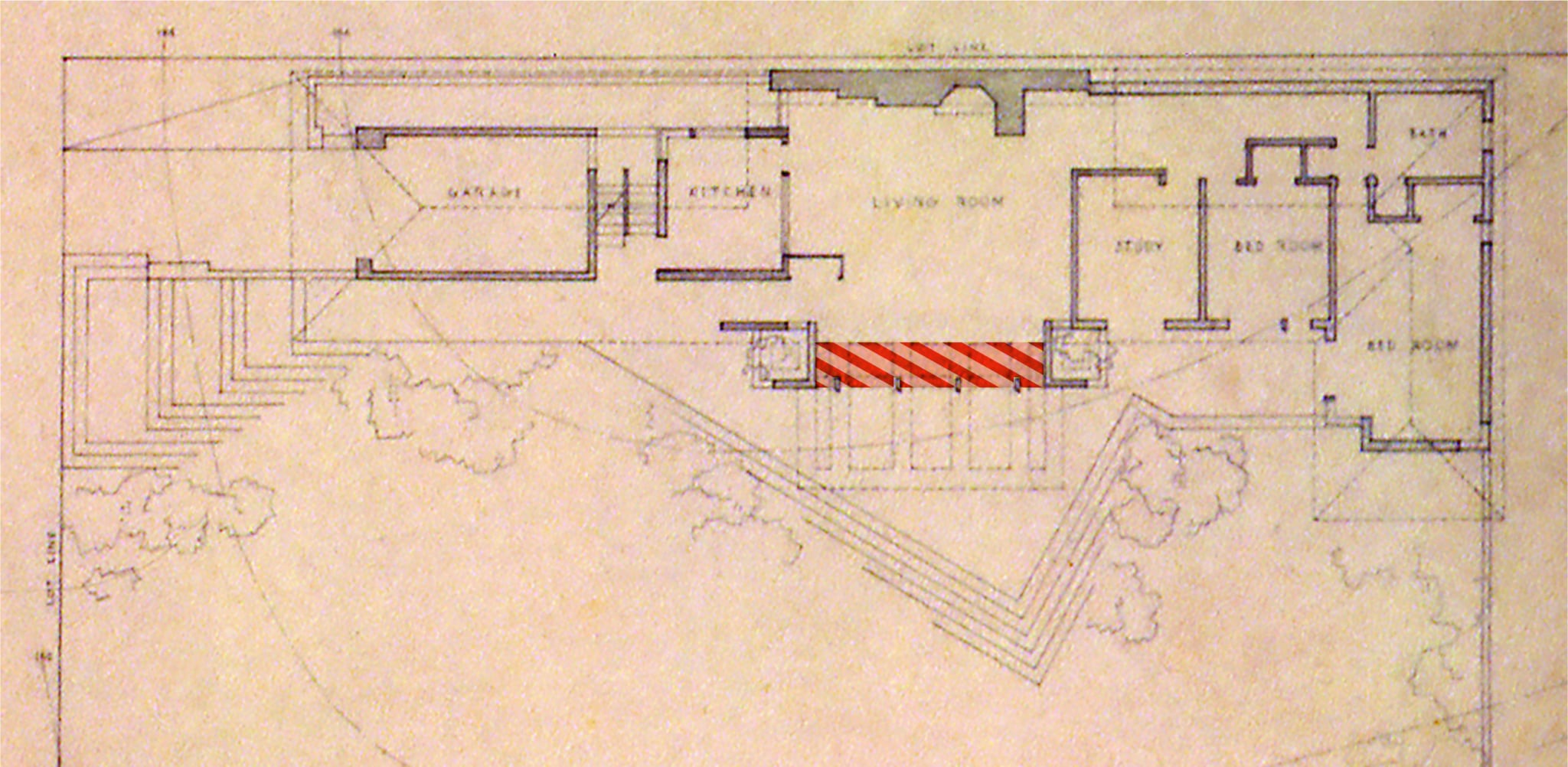

Venn Diagram

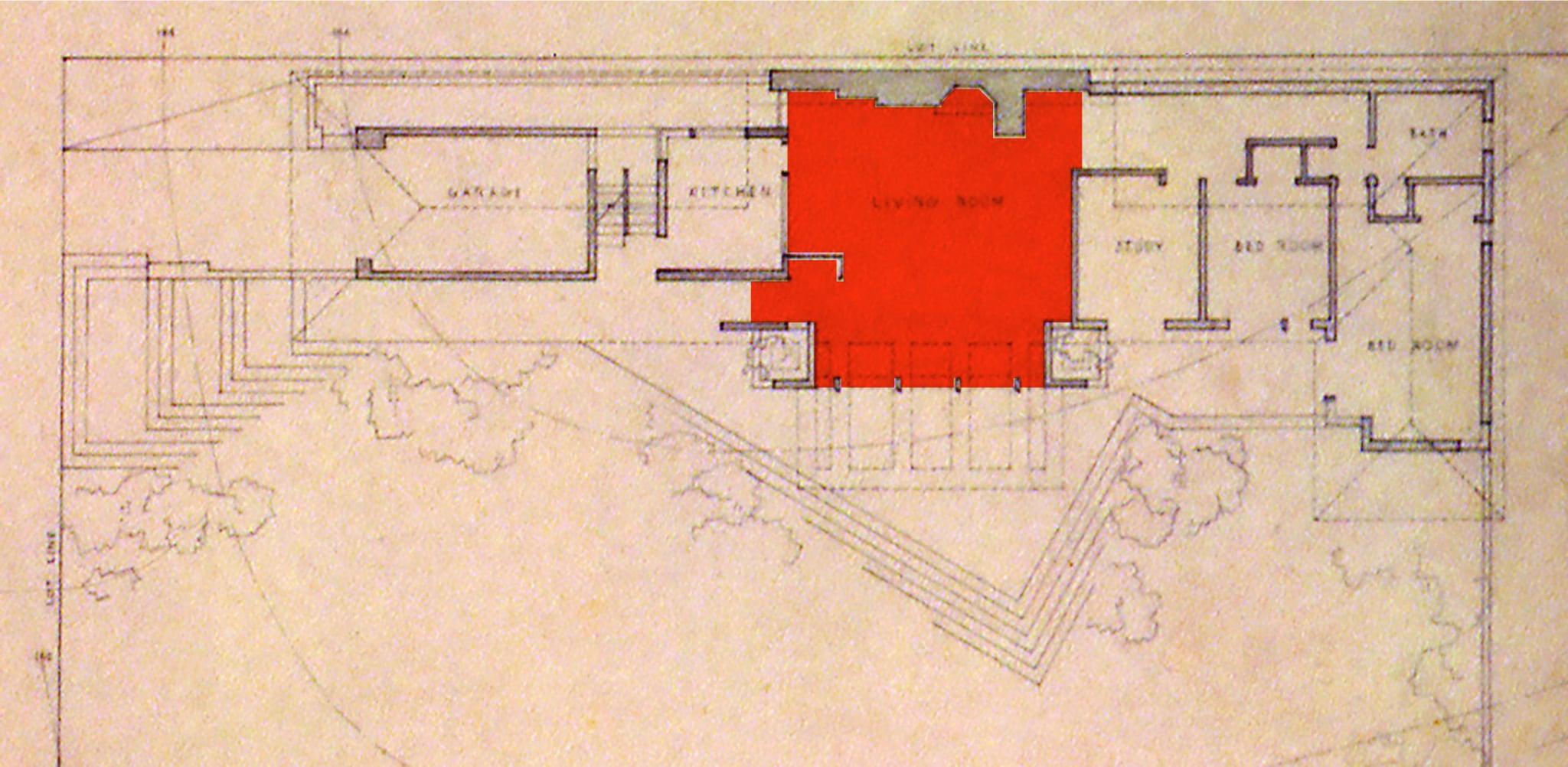

Something Levine didn’t mention was a clue Wright left for us in plain sight. It explained exactly what he was attempting to do at Willey. He embedded a Venn diagram into the plan that was ultimately realized in red brick. This figure is evident in plan view and remarkably obvious in its physical manifestation on the floor of the living room. Yet no one has ever made mention of it.

Venn Field 1.

Venn Field 2.

Venn Field 3.

Wright defined the interior space of the living room bounded by perimeter and partition walls. (Field 1) The terrace delineates the defined exterior space, an extension of the living room floor. (Field 2) The area of overlap between fields belongs to both. (Field 3) The overlapping space is equal parts indoors and outdoors. Notably, this is the zone above which the skylights are set. Skylights are identical in width to the interstitial spaces between the outdoor trellis arms. And home to the wall of French doors. Year-round, large glass panels draw in the garden. But when the bank of doors are swung open, as they were when the Willeys experienced a lovely summer day, the living room is fully transformed into an open-walled pavilion placed in a park-like setting. The shared zone is the most liminal of spaces.

The Labyrinth

Wright’s entry sequences have been referred to as “labyrinthine,” meaning they are indirect to an extreme. Often purposely intricate, winding or complex processions featuring twists and turns intended to create a gradually unfolding experience for the guest as inner spaces are revealed.

But the term labyrinth is a contranym, a word with two opposite meanings. Though both could apply to Wright’s use of space, it is the less obvious meaning that is most relevant.

Dictionaries invariably define a labyrinth like this example from Merriam-Webster:

- a place constructed of or full of intricate passageways and blind alleys a complex labyrinth of tunnels and chambers

- a maze (as in a garden) formed by paths separated by high hedges

- something extremely complex or tortuous in structure, arrangement, or character : intricacy, perplexity

- a tortuous anatomical structure especially : the internal ear or its bony or membranous part

Invariably, dictionary definitions connote a confusing series of winding passageways. So it should come as no surprise that is what we believe a labyrinth to be. Even the familiar Greek myth of the Minotaur describes a vast, presumably subterranean, imprisoning structure built by the architect Daedalus, for King Minos of Crete. The King had an illegitimate son born half-man half-bull. This monster, the Minotaur needed to be “kept” and so was placed in the center of a labyrinth, which effectively prevented his escape. To keep him satisfied inside, each year seven young men and seven young women were sent into the labyrinth as sacrifice to be devoured by the Minotaur.

On the year Theseus fell in love with Ariadne, he was selected as sacrifice. Trusting in his swordsmanship more than his sense of direction, Ariadne gave him a ball of thread to unwind as he entered, so if he was successful in slaying the Minotaur, he could follow the thread back to her again.

As the story goes Theseus bests the monster and thanks to the string trail, retraces his steps out of the labyrinth. The guided path he followed is known as “The Thread of Ariadne.” All labyrinths represent this thread. This is the second meaning of labyrinth, a guided path. Labyrinths are not meant to confuse. We can leave that to the maze, an invention meant to confound and frustrate. A labyrinth, like The Thread of Ariadne is a serpentine, guided path, meant to direct.

The layout of the labyrinth imbedded into the floor of Chartres Cathedral.

The earthen Chartres labyrinth at Potter’s Farm in far northern Wisconsin. Photo by Steve Sikora.

An 11-circuit Chartres labyrinth requires approximately 425 small steps to reach the center. I know this because I maintained one in Northern Wisconsin for over a decade. It is so named because one of its kind, but not the first, was used on the floor of the cathedral at Chartres, France. 425 steps in, and 425 steps back out again. The distance is known as “the league” in Chartres. Even though a traditional 11-circuit labyrinth is just under 41 feet in diameter, 12.455 meters to be exact, the path to the center is over an eighth of mile in length, a model of spatial efficiency. The original Chartres labyrinth laid into the cathedral floor and dedicated in the year 1260 is still a modern, appropriated interpretation of an ancient form. It is ornate and embedded with religious and mythical symbolism that a simple earthen version would never possess. But all labyrinths, regardless of age, design or geographical location share one essential thing in common. They are all unicursal paths that persistently recurve upon themselves again and again in a serpentine motion.

They have been compared to the birth canal, a winter hibernaculum of a burrowing animal, the mortal coil of a lifetime, a dance wheel, an ideogram of the sun’s path, the orbit of Mercury, the pilgrimage to the heavenly Jerusalem, and a journey of personal discovery among many others. In truth, no one knows the original meaning of labyrinths.

Despite the fact that they appear on nearly every continent, they predate all historical record. While their original purpose has been lost to time, their appeal has not been. Herman Kern’s massive tome on the subject Through the Labyrinth, is as weighty and well-researched as any text one could imagine on the subject, but reading it will get you no closer to the answer of purpose. One thing is certain and Wright was aware of it. There is something tangible, yet indefinable about walking the directed path of a labyrinth that must be experienced in order to fully grasp.

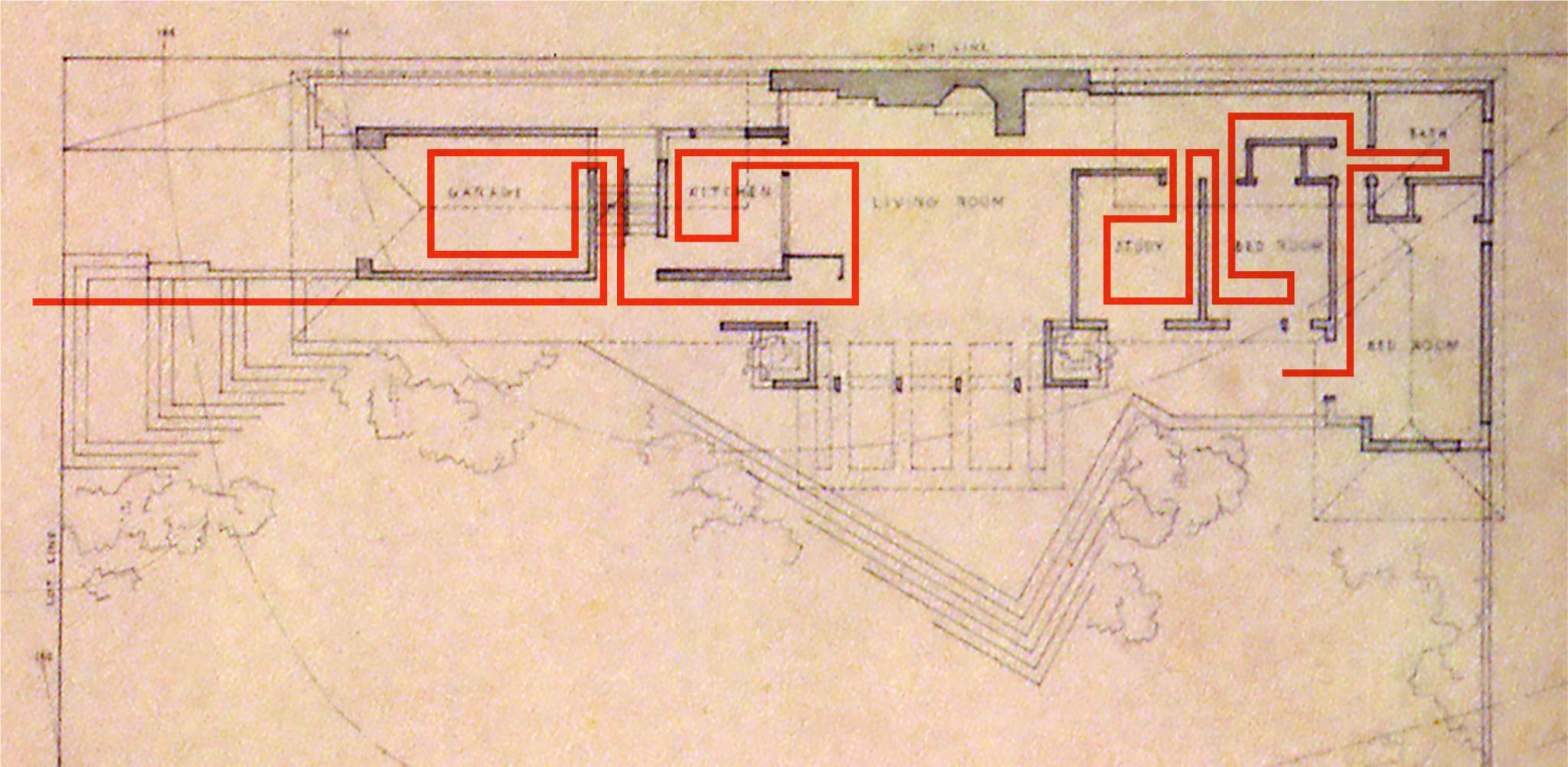

In the context of Wright buildings, the Willey House has a relatively direct entry sequence but the labyrinth metaphor still applies when defined as a guided pathway, the Thread of Ariadne. I didn’t realize this until I traced the line we intuitively follow when hosting tour groups visiting the house and learned it is possible to visit every room in sequence without once crossing over your own path.

Like the “thread of Ariadne” found in a labyrinth, a unicursal path exists at the Willey House that courses from one end of the house to the other.

At the Willey House, the utter simplicity of the entry procession promotes the mistaken belief that the structure is far more predictable than it actually is. Upon approach, a guest can easily grasp the external shape of the house, and are comforted with the anticipated sense of the general layout inside. Sure enough, the journey from the West end to East end is intuitive and direct. Unexpected however, is the total effect of Wright’s shaped spaces. His diaphanous screens play off imposing brick masses, vistas appear inside and out all directions, and hyperactive ceilings levitate over floating decks that make each subsequent step a fresh, visceral delight. Willey’s unfolding mysteries tickle the imagination as interior spaces gradually manifest, then proceed to transform themselves, as the visitor steps from one side of a room to another. While the promise of the house holds familiarity and reassurance, the actuality of the experience is a thrill-ride of discovery at every turn.

Read all of “The Space Within” blogs for this special five-part Willey House feature:

- Part 1: Little Boxes

- Part 2: Vista Inside and Out

- Part 3: Sense of Shelter

- Part 4: Sense of Space

- Part 5: The Purpose