In 2003, writing about the audio production setup behind the 45th Annual GRAMMY Awards telecast for the first time, I observed, “It takes a village to put together a show like the GRAMMYs.” That year’s live music showcase, held at Madison Square Garden in New York City, was the first ever primetime terrestrial broadcast of an awards show in HDTV with 5.1 audio, several years ahead of the government-mandated switchover from analog to digital broadcast transmission.

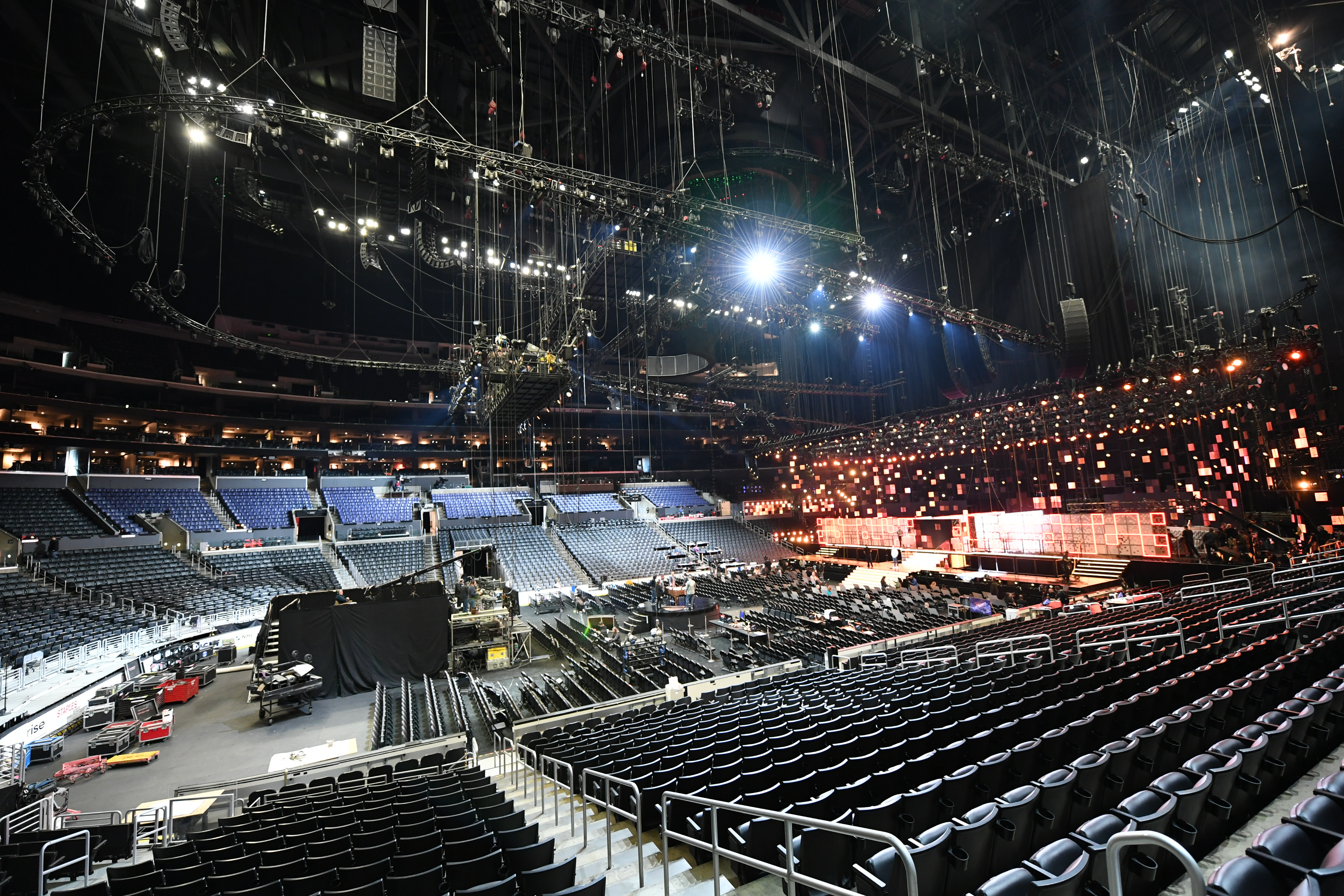

This year, the telecast returned to the 21,000-capacity Staples Center arena in downtown Los Angeles, the awards show’s longtime home, after last year’s rare visit to New York. Whether in L.A. or New York, the audio setup is complex, making full use of the six days typically allocated for load-in, soundchecks, camera blocking, full production run-through and live broadcast. And every year, the audio production setup for the GRAMMY Awards telecast takes incremental steps forward in terms of workflow, efficiency, failure mitigation and quality as new technologies and products are assimilated.

“We have 16 stage floor A2s, two foldback mixers and six stage assistant engineers,” says Michael Abbott, who has been head of audio for the GRAMMY production for several decades. “At front-of-house there are five engineers, including two mixers. In the [music mix] trucks there are three engineers each—a mixer, recordist and an assist. And we have two standalone Pro Tools systems, allocated to one stage each” for playback of tracks as well as clicks and counts for the artists and show automation timecode, where needed.

Overseeing all aspects of the audio production are three advisors from the Recording Academy’s Producers and Engineers Wing. Recording engineer, producer and GRAMMY Telecast Advisor for Broadcast Audio Ed Cherney sits with on-air TV production mixer Tom Holmes in the broadcast truck parked in the below-ground loading bay. Leslie Ann Jones, Director of Music and Scoring at Skywalker Sound and GRAMMY Telecast Advisor for House Audio, works with the house sound crew. Producer, engineer, composer, studio owner and educator and GRAMMY Telecast Advisor for Music Mix Audio Glenn Lorbecki provides quality control of the broadcast music mix, including monitoring the backhaul from CBS on the East Coast to ensure consistency all the way to the viewer.

Over the years, the production has been incrementally adding people to tackle the technical complexities and cover all the bases should there be a problem; this is a live broadcast, after all. “It’s trying to rise to the challenge, with one looming factor in the background—failure mitigation,” says Abbott. Things don’t always go smoothly but Abbott and his team do everything they can to reduce the potential for failure—no, you can’t load your presets into the monitor console from your USB drive—while also accommodating the needs of the artists.

California-based ATK Audiotek has long provided the audience front-of-house and artist monitoring systems for the L.A. telecasts. For this year’s show, the provider fielded JBL’s newer VTX A12 line array elements for the main hangs and delay clusters.

“The approach is to try and keep as much of the room from affecting the broadcast as possible,” says Jeff Peterson, Audiotek’s system engineer, during setup. Year to year, he says, “The equipment sometimes changes; things get lighter, more efficient and easier to fly.”

Because the PA typically must be trimmed a little higher than usual to clear the sets and sightlines, “On the bottom of all our main clusters we’re using the new A12 Wide, a wide pattern of the A12 line,” he says, eight in total. “It’s 120 degrees wide, so we don’t have a hole in the center of the room. It also covers better on the sides, where the main left and right overlaps with the out fills.”

Four clusters of eight VerTec 4886 modules cover the upper seating levels, with four delay clusters of VTX A12s covering the upper rear seats. “This year they’ve added a seating section on either side of the stage. We’re covering those with JBL’s new A8, a small cluster of four” per side, he says.

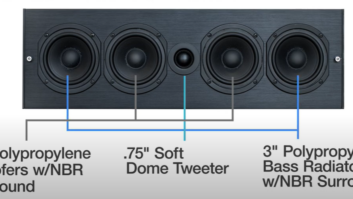

Front fills ensure that the imaging is anchored to the stage. “You don’t want to hear a concert coming from 40 feet overhead.”

Sixteen JBL S28 subs and eight JBL B18 subs below the stage lip provide a comfortable level of low frequency energy. “We don’t hang enough subs to do a hip-hop concert. Because we’re not aiming for 115 dB at front-of-house, we’re not flying that many,” says Peterson, also noting that there are weight and power restrictions.

Nineteen Crown Audio I-Tech 4x3500HD amps power the line arrays with six I-Tech 12000HDs behind the subs. “It’s all controlled through Performance Manager software and processed in the amplifiers,” he says.

A network of six Optocore DD32R-FX and two DD4MRFX units provides PA drive. “It’s been a rock-solid platform for 10-plus years. It carries the control network along with the audio. We run one ring of fiber,” says Peterson.

An Optocore network supports PA drive. “It’s been a rock-solid platform for 10-plus years. It carries the control network along with the audio. We run one ring of fiber,” says Peterson.

“This is not a loud show; we run between 95 dB and maybe 104 dB,” confirms veteran GRAMMY FOH music mixer Ron Reaves. There have been exceptions, he recalls: “AC/DC was 116 dB for six minutes,” on the 2015 show.

Typically, the production wrangles 300 to 350 microphones, wired and wireless, including those for the announcers and to capture the audience, plus 30 or so line-level inputs. To allow quick changeovers of the often-elaborate sets there are two main stages, designated A and B, plus a circular satellite stage on the arena floor for soloists and small ensembles.

Backstage, Soundtronics of Burbank, CA, has long provided RF coordination and manages the artists’ vocal mic and other wireless needs, which generally total in excess of 50 channels. This year the wireless provider relied heavily on Sennheiser Digital 6000 and Shure Axient Digital RF mic systems, with the new Audio-Technica 5000 series also available, and deployed its proprietary antenna system to cover all three stages.

All the mics and lines from stage, plus the two Pro Tools playback rigs, go through Split World. There, engineer Steve Anderson oversees their distribution via Calrec Hydra2 transport to Holmes in the broadcast truck, via Lawo Dallis racks to the two M3 Music Mix Mobile trucks, parked outside, that mix all the music performances in 5.1, and the FOH and monitor positions.

Reaves mixes the music performances for the audience on a DiGiCo SD7. “I have 168 open faders plus eight stereo effects returns and some miscellaneous channels,” says Reaves, noting that he’s never had to use them all. To his left, Mikael Stewart manages all the production elements for the house, such as announcers, video package playback tracks and so on, through an SD5.

A DiGiCo S21 stands by in case Stewart’s console has a critical failure. “That console lands a full production mix from the [broadcast] truck, without audience mics, and a music mix from Ron, so that if Stewart’s console crashes, I can switch the system drive inputs over to that backup console,” says Peterson. Those lines are transported between the truck and FOH using a Lance Designs Cobranet system, deployed for the first time this year. In the opposite direction, lines from FOH are available to Holmes should the truck’s Calrec broadcast console have a critical failure.

Audiotek switched to DiGiCo in 2012, at that time bringing in six, including a backup each for monitor mixers Tom Pesa and Mike Parker, positioned at opposite sides of the arena, plus two at FOH. These days, Pesa and Parker each have just one SD7 positioned side-by-side behind the set and, while still responsible for separate stages, can take over from the other in case of a failure. All four DiGiCo desks are networked, offering access to eight 56-input SD-Racks. Another four SD-Racks provide monitor outputs, principally driving in-ears but also wedges for some artists including, this year, Dolly Parton.

While artists often bring their monitor engineers with them and they may be familiar with the SD7, they generally leave the mixing to Pesa and Parker. “They can have facetime with their artist, have a conversation and relay anything to me and I can quickly get anything done that they need,” says Pesa.

The production accommodates a small handful of artists who prefer to bring their entire monitor rig, although that obviously adds to the production’s complexity. There was one additional monitor setup this year; last year there were seven.

In the M3 music mix trucks, each equipped with a Lawo mc²56 48-fader console, mixers John Harris and Eric Schilling both have access to all 168 inputs. In the past, one of the engineers would mix one artist’s rehearsal in one dedicated truck while the other fine-tuned another performer’s earlier run-through—the trucks are each outfitted with dual 192-channel Pro Tools HDX systems—with that artist’s representatives in the other truck. On the night of the show, the pair would alternate at the desk feeding Holmes in the broadcast truck.

Beginning last year, both desks now mix rehearsals and the show, with Schilling handling the A stage and Harris the B stage, removing the need for the engineers to move between the M3 trucks. “We can really make a nest and stay in it. It’s a little incremental evolution,” says Harris.

The new workflow also strengthens the all-important failsafe issue. “By the time the show starts all my scenes will be in [Eric’s] desk and all his will be in this one,” he says, should either need to take over in an emergency.

In past years, M3 deployed racks of Grace Design and Aphex preamps at Split World where an operator—most recently, longtime Pro Sound News contributor Russ Long—would manage the levels. Those are now gone; instead, Harris and Schilling have individual control of the Lawo preamps in the Dallis racks. “Now I have more of a tactile connection, which I like; that’s the way I grew up,” says Harris.