Revisiting Midway Gardens

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation | Jun 27, 2018

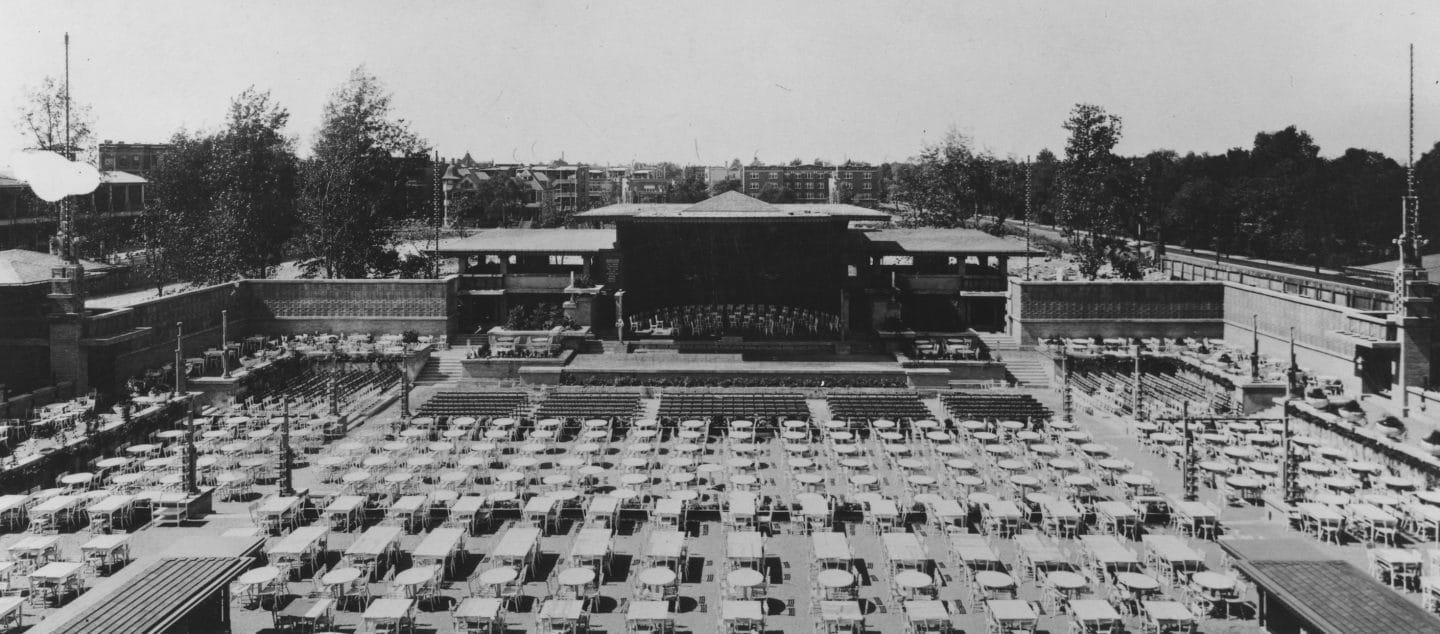

On June 27, 1914, in Chicago, Midway Gardens—a concert garden with space for year-round dining, drinking, and performances—opened to the public.

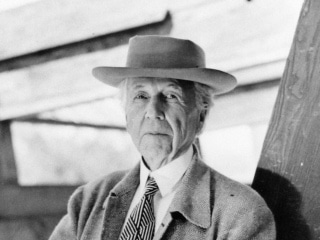

Although its existence was brief—it was demolished in 1929—Midway Gardens hosted several notable performances, and was, in all aspects down to the napkin rings, a Frank Lloyd Wright design. In the following excerpts from “The Tale of the Midway Gardens” of Book Three of “An Autobiography,” Frank Lloyd Wright details the imaginative creation of Midway Gardens.

Some time ago, it was in the fall of 1913, young Ed Waller’s head got outside the idea of the Chicago Midway Gardens and he set to work. First on me. One day when I had come into Chicago from the Taliesin studio-workshop, he began on me.

Said Ed: “Frank, in all this black old town there’s no place to go but out, nor any place to come but back, that isn’t bare and ugly unless it’s cheap and nasty. I want to put a garden in this wilderness of smoky dens, car-tracks, and saloons.”

This sounded like his father whom you have seen in the experience with Uncle Dan in the library of the house at River Forest.

“I believe Chicago would appreciate a beautiful garden resort. Our people would go there, listen to good music, eat and drink. You know, an outdoor garden something like those little parks round Munich where German families go. You have seen them.

“Well, Aladdin and his wonderful lamp had fascinated me as a boy. But by now I knew the enchanting young Arabian was really just a symbol for creative desire, his lamp intended for another symbol—imagination.”

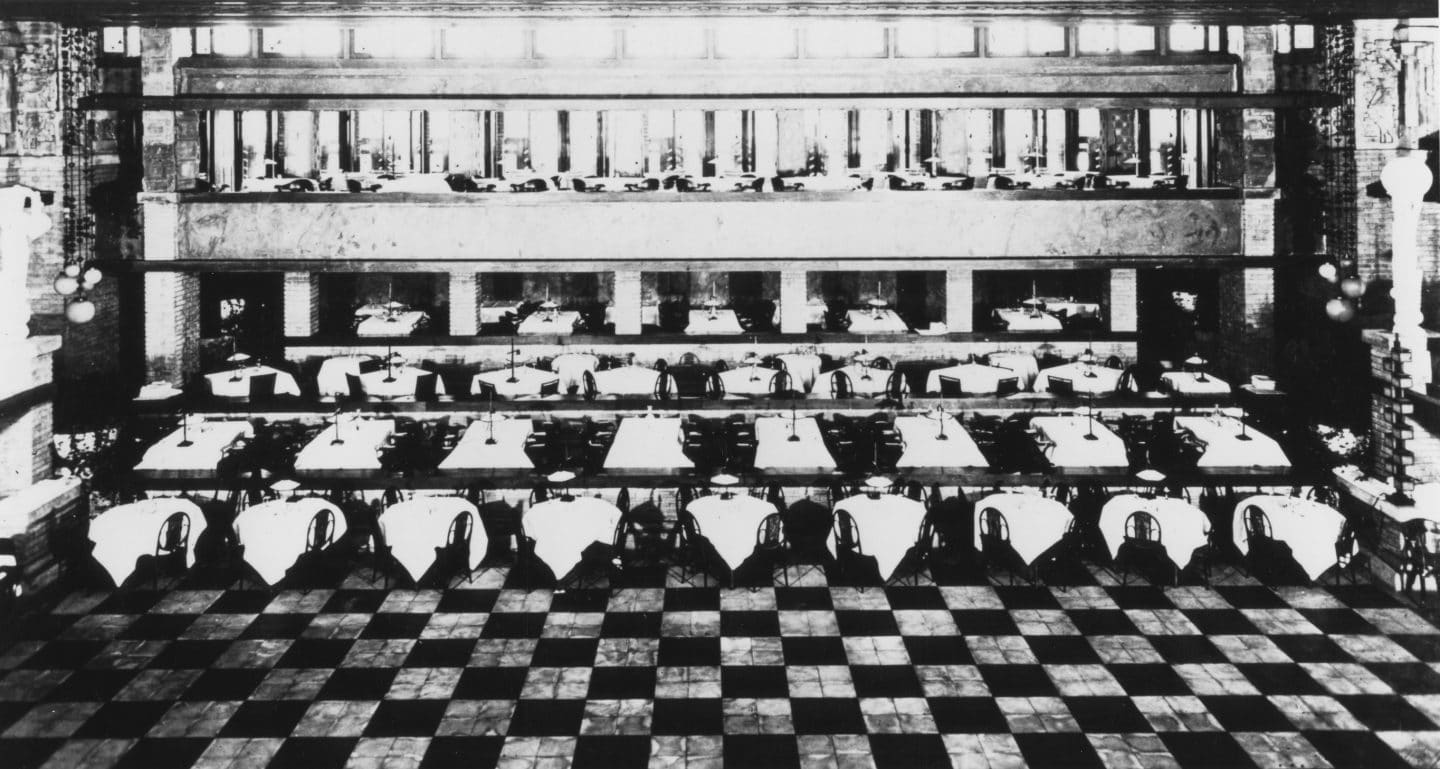

“The dance craze is on now, too, and we could have a dancing floor inside somewhere for the young folks. Yes, and a place within the big place outside near the orchestra where highbrows could come and sit to hear a fine concert even if they did want to dine at home.

“The trouble of course is the short season. But we could fix that up by putting a winter-garden on one side for diners, with a big dancing floor in the middle. And to make it all surefire as to money we would put in a bar [the “affliction” had not yet befallen] that would go the year around. We would run the whole thing as a high-class entertainment on a grand scale—Pavlowa dancing—Max Bendix’s full orchestra playing-you know Max. Music outdoors starting at seven o’clock. Between orchestral numbers there would be a dance-orchestra striking up, back there in the winter-garden, so the girls could get the boys to dance. Special matinees several days a week. Features every night. I see people up on balconies and all around over the tops of the buildings. Light, color, music, movement – a gay place!

“Frank, you could make it unique,” he went on.

“I know I could,” I said, “where I can get the ground. Down on the South Side just off the Midway. The old Sans Souci place. Been on the rocks for years. Stupid old ballyhoo. It’s just big enough, I think. About three acres. You’ll get paid for your drawings anyway.”

All Ed didn’t know was where he could get the money. He said “but that is the easiest part of it.” He would fix that.

“What do you think of the idea?”

Well, Aladdin and his wonderful lamp had fascinated me as a boy. But by now I knew the enchanting young Arabian was really just a symbol for creative desire, his lamp intended for another symbol—imagination. As I sat listening I was Aladdin. Young Ed? The genii. He knew apparently where all “the slaves of the lamp” could be found. Well, this might all be necromancy but I believed in magic. Had I not rubbed my lamp with what seemed wonderful effect, before this? I didn’t hesitate.

“When you get back to the office, Ed, send me a survey of the old Sans Souci grounds. Then come back Monday,” I said. “You’ll see what . . . you’ll see.”

He came back Monday. The thing had simply shaken itself out of my sleeve. In a remarkably short time there it was on paper—in color. Young Ed gloated over it.

“I knew it,” he said. “You could do it and this is it.”

. . .

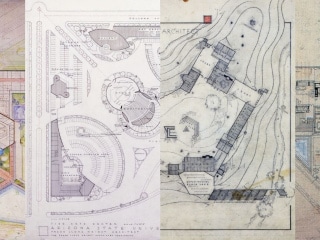

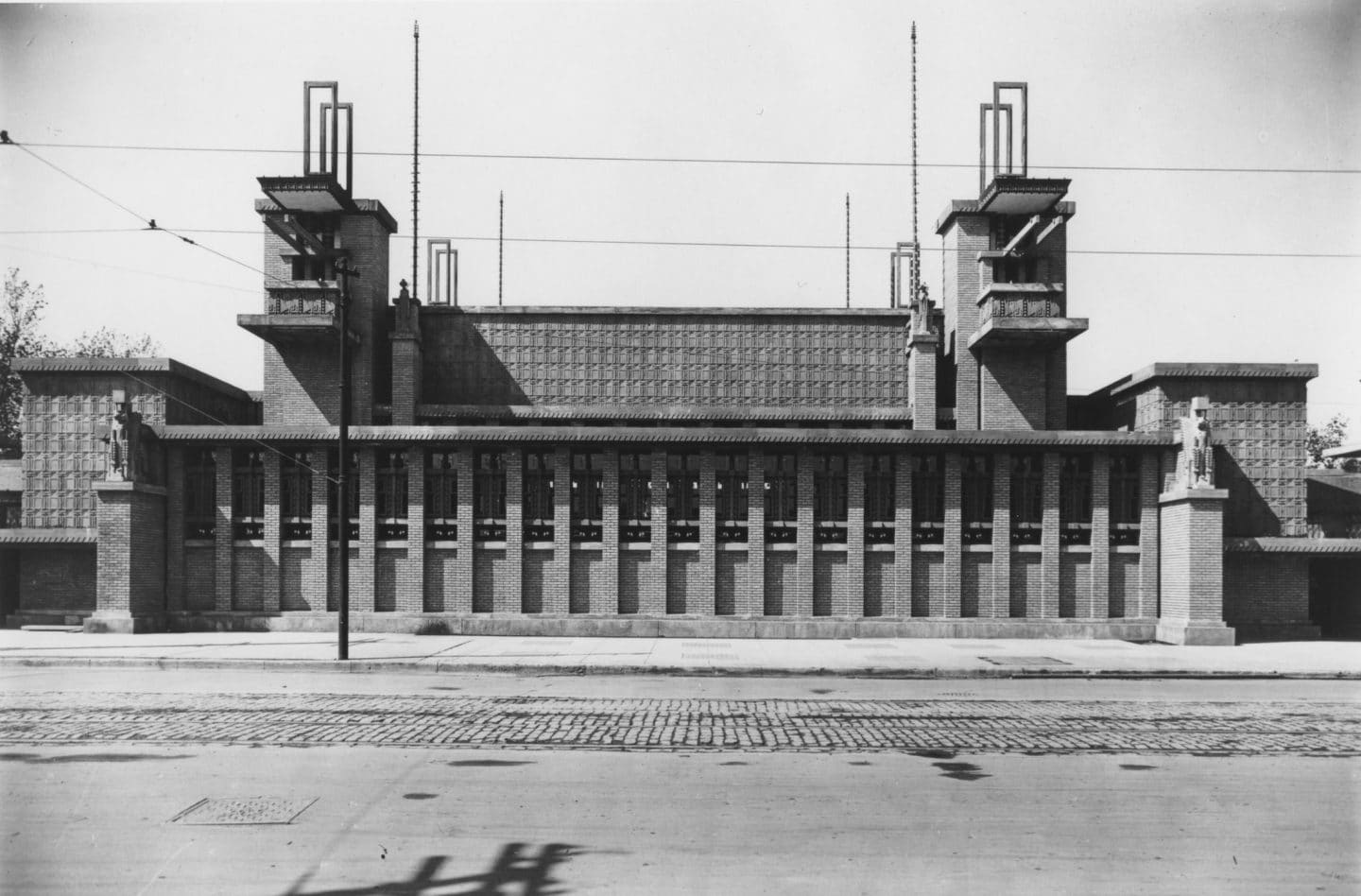

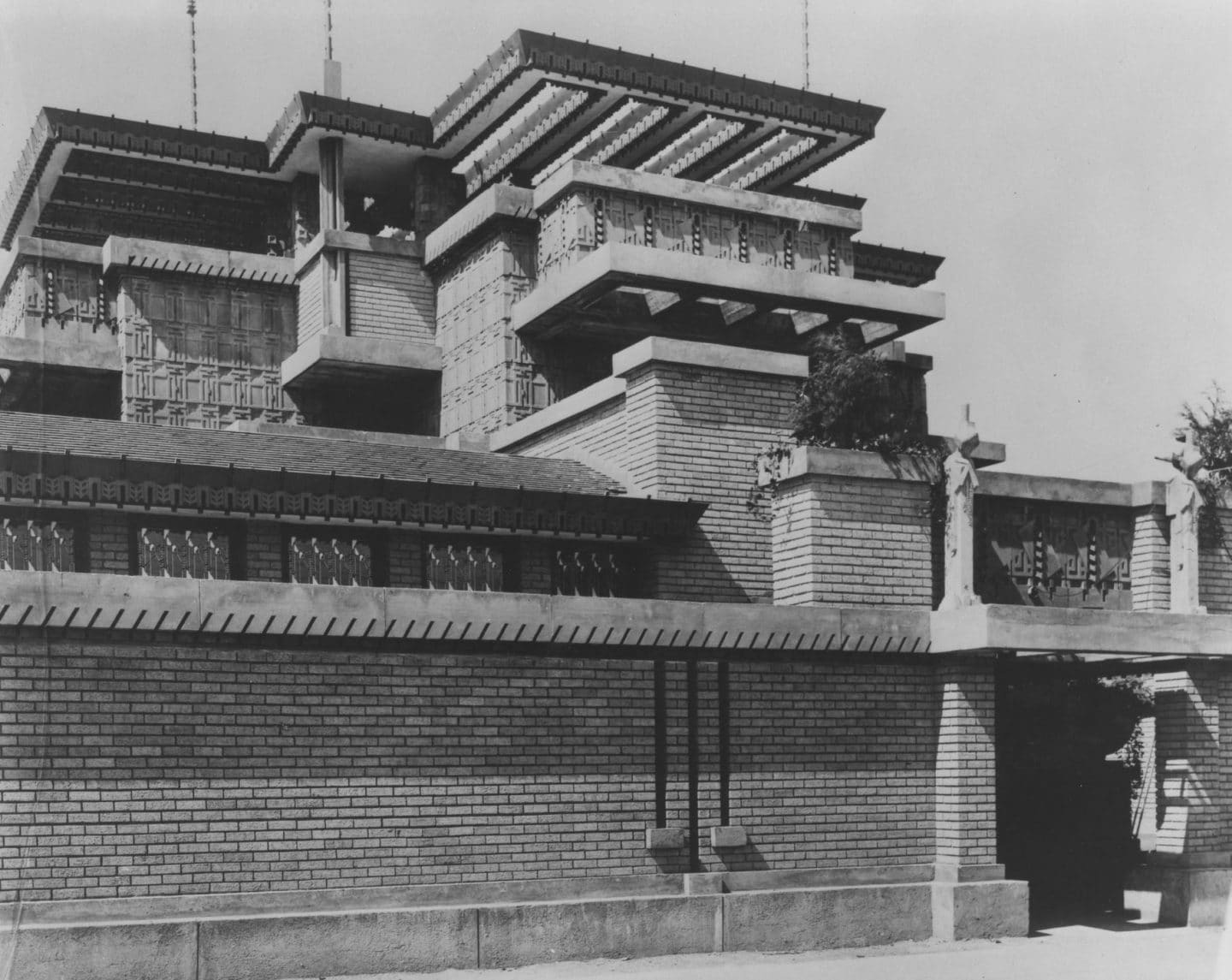

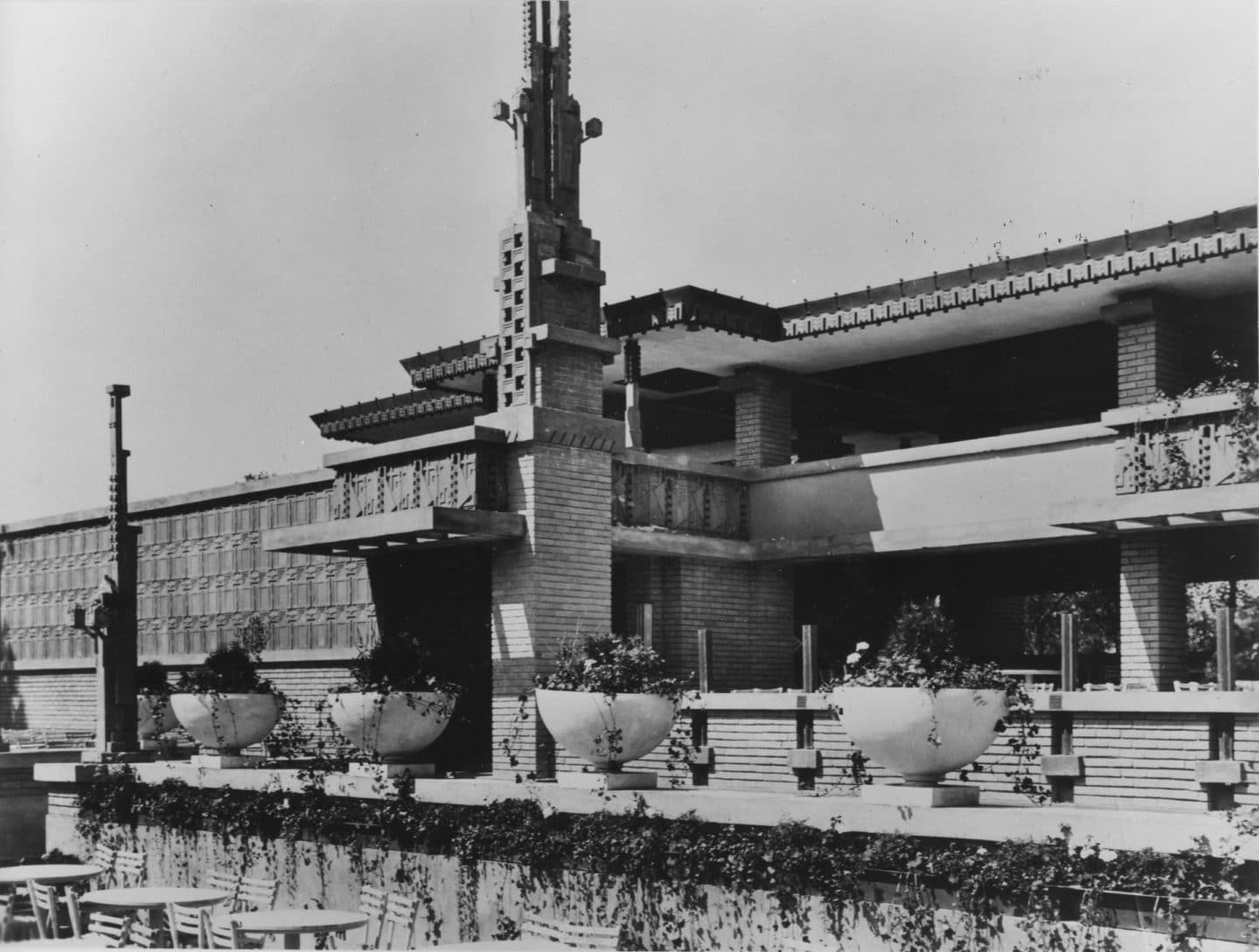

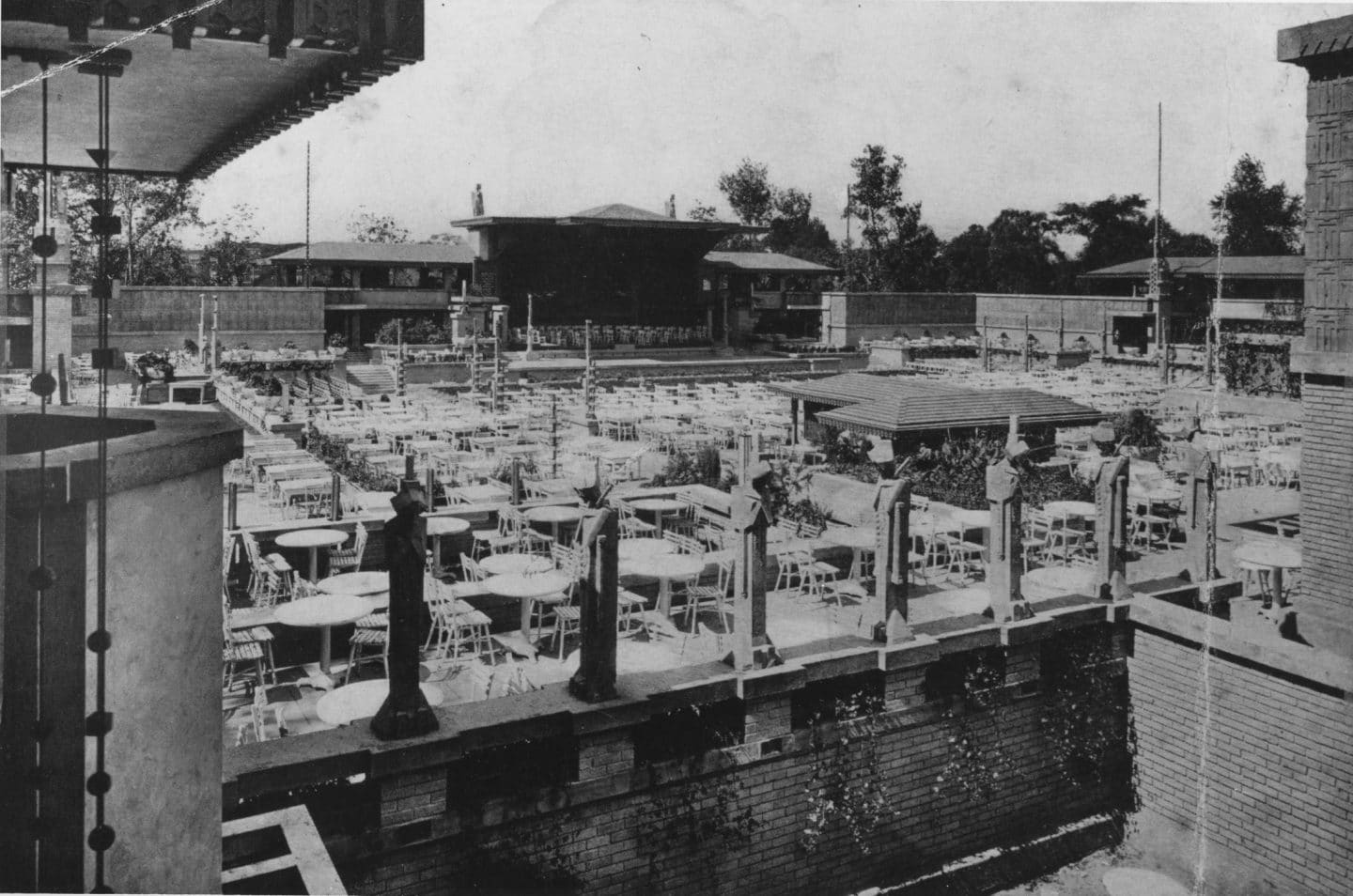

The Midway Gardens were planned as a summer garden: a system of low masonry terraces enclosed by promenades, loggias and galleries at the sides, these flanked by the Winter Garden. The Winter Garden also was terraced and balconied in permanent masonry without and within. This Winter Garden stood on the main street, opposite the great orchestra shell. The Bar, “supporting economic feature,” was put on the principal corner. Ed argued that a bar should be right across a man’s path, a manifest temptation. That boy knew a lot about human weaknesses-among other things. This bar, as manifest temptation, was going strong when the nation-wide affliction befell.

At the extreme outer corners of the lot toward the main street were set the two tall welcoming features, flat towers topped by trellises intended to be covered with vines and flowers and ablaze with light to advertise the entrances to both summer and winter gardens. The kitchen, of course, as stomach is to man, was located beneath and at the very center of the building scheme, short tunnels leading direct to the Gardens for quick service, service stairs leading straight up into the winter-garden terraces above it. A waiter could with reasonable ease get direct to all the various terrace levels, balconies and roofs. And the waiters were legion.

Midway Gardens Sprites

Frank Lloyd Wright sought the help of sculptor Iannelli in incorporating sculpture and art “back again to their original places and to their original offices in architecture, where they belonged,” for Midway Gardens. The sculptures, known as Sprites, were placed throughout the site.

Today, drawing on inspiration from the now demolished site, you can incorporate the sculptures into your home with reproductions from the online Frank Lloyd Wright Store. Shop online or call 480.627.5398 for more information.