A Powerful Brand: Marion Mahony’s Original Form of Graphic Representation

Jennifer Gray | Feb 14, 2022

Jennifer Gray examines the importance and contributions of Marion Mahony, the artist responsible for creating Frank Lloyd Wright’s signature style of representation in the early years of his career.

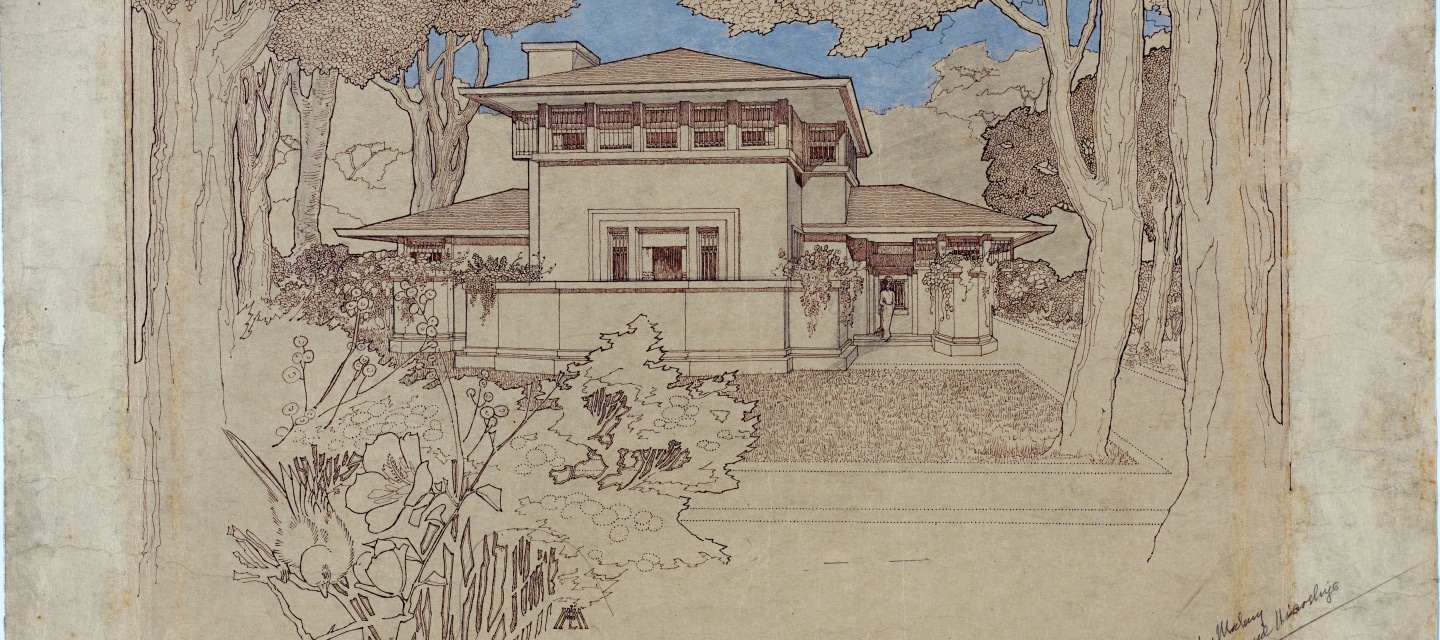

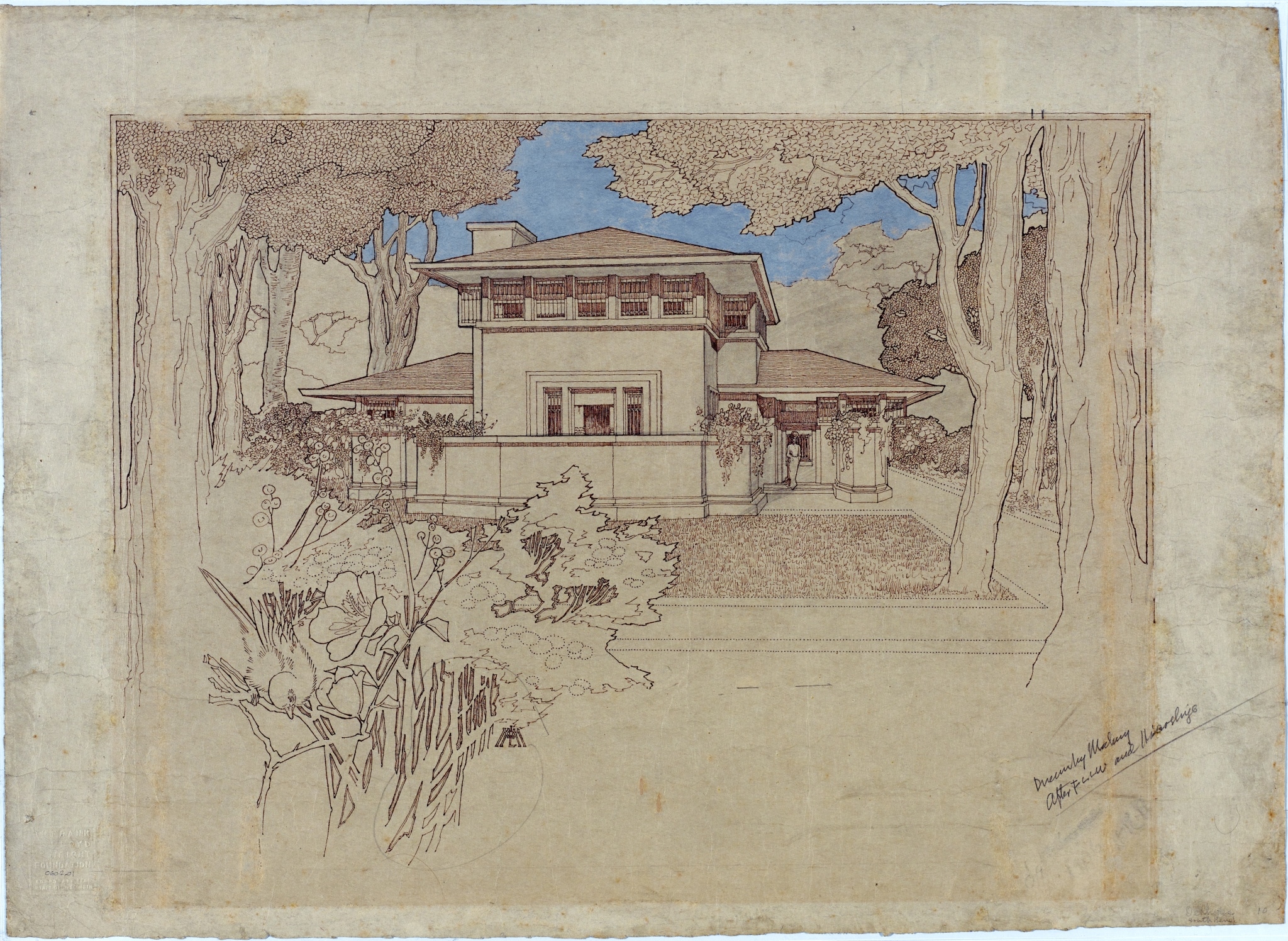

In 1906 Marion Lucy Mahony produced a presentation drawing for the K.C. DeRhodes House in South Bend, Indiana, that was so remarkable it prompted Frank Lloyd Wright to annotate the sheet “after FLLW and Hiroshige” in an attempt to demonstrate its “indebtedness to Japanese art while also desperately trying to make it his own.”1 But the real author is revealed by the monogram—MLM—tucked into the foreground foliage. Mahony was Wright’s first employee, finest draftsperson, and the artist responsible for creating his signature style of representation in the early years of his career. Unpacking her drawings tells us about the important and unconventional role women played in Wright’s practice at the turn of the century.

The DeRhodes House rendering is considered by many to be the first completely realized drawing in Mahony’s new style. Breaking from convention, she integrates architecture and nature into the same linear composition, borrowing several techniques from Japanese prints to create a powerful brand identity for marketing Wright’s architecture for clients but also for the world through reproductions in journals and prints. Marion Mahony, renderer; Frank Lloyd Wright, architect. DeRhodes House, South Bend, Indiana. 1906. Perspective. Ink, pencil, and colored pencil on paper. 18 1/2 x 25 3/4 in.

It is not an exaggeration to say that Mahony was in the vanguard of architecture and women’s rights. Mahony joined Wright’s office in 1895, after graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the second woman ever to be awarded an architecture degree from that institution. In 1898 she became the first woman licensed to practice architecture in Illinois. Her personal and professional circles in Chicago were unapologetically progressive and feminist.2 Unlike Wright, who never formally studied architecture, Mahony had trained in standard rendering formulas at MIT. During these years, Wright frequently commissioned presentation drawings from freelance renderers, and initially he assigned Mahony to make technical working drawings. But as her talent for presentation drawing became apparent, Wright began asking her to draw renderings, including for Unity Temple, one of his most important projects.3

The DeRhodes house drawing is an exemplar of Mahony’s original form of graphic representation, which challenged rendering conventions of the time, including those she learned as an architecture student. Her extraordinary feel for line can be seen in the way she integrates the architecture entirely with the natural world, part of the same continuous linear composition. Much of the foliage is depicted as individual leaves and blades of grass, drawn as sharply as the building and in the same plane. Depth and emphasis are indicated by varying the line weights rather than changing the tone of applied washes.4 Several compositional techniques are derived from Japanese prints: the trees that break the picture plane, for example, as well as the use of negative space, unusual perspective, and abrupt changes in scale, such as the close-up bird and flowers in the foreground as they relate to the house behind.

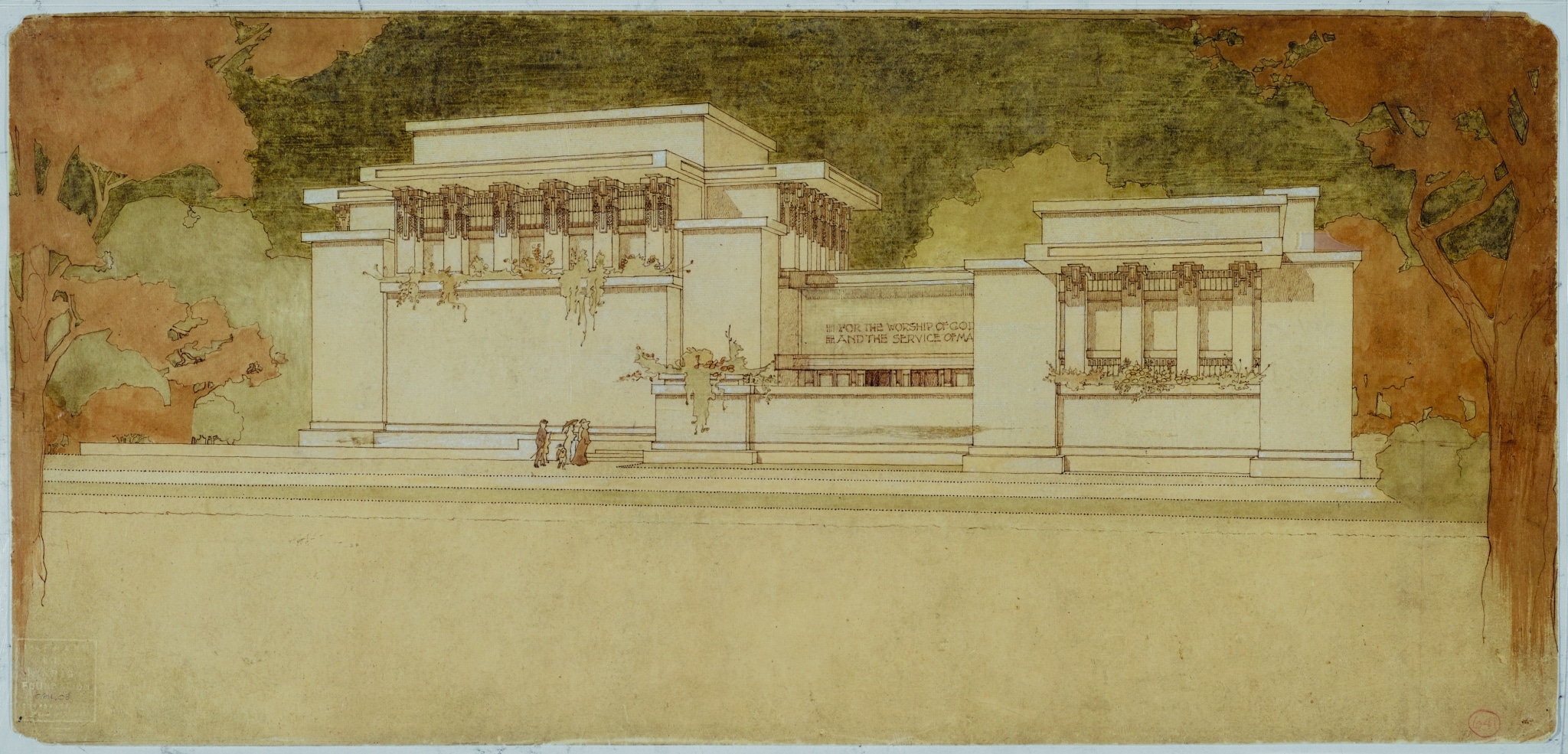

Mahony’s breakthrough rendering for Unity Temple demonstrates her unparalleled feel for line in the way she articulates the building while ignoring the background. Though still using conventional applied washes for the foliage, the emergence of her original drawing style can be seen in the way the trees break the picture plane, the use of negative space at the bottom of the composition, and the subtle worm’s eye perspective. Marion Mahony, renderer; Frank Lloyd Wright, architect. Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois. 1905-08. Perspective. Watercolor and ink on paper, 12 x 25 1/8 in.

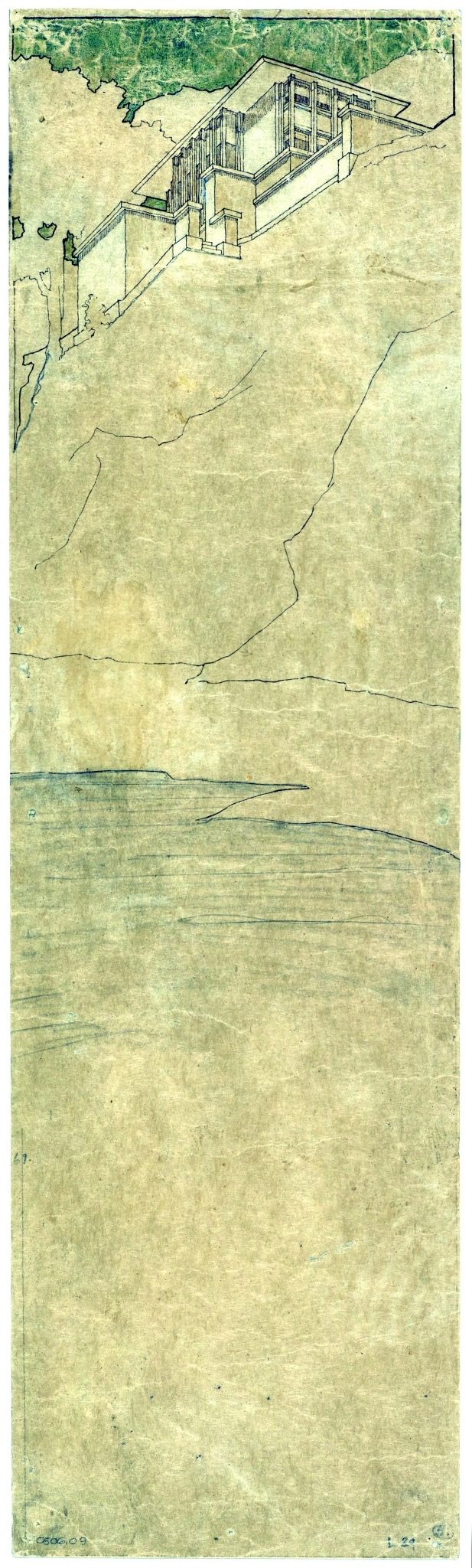

The significance of Japanese prints for Mahony is evident in this extraordinary drawing of the Hardy House. The house was perched atop a precipitous ravine that descended into a lake. Mahony employed an unusually strong worm’s eye perspective and vertical composition to emphasize the house’s spectacular natural setting. The composition is so forceful, the architecture almost reads secondary to its surroundings except for its detail and highlighting compared to the abstract landscape. Marion Mahony, renderer; Frank Lloyd Wright, architect. Hardy House, Racine, Wisconsin. 1905. Perspective. Watercolor, ink, and pencil on paper. 18 3/4x 5 3/8 in.

Wright made the connection to Japanese art explicit when he annotated the drawing to reference Hiroshige, one of the last masters of the woodblock print whose work the architect was collecting and exhibiting at this time. But whatever belated claims to authorship Wright attempted by scrawling his own initials onto the drawing, it is clearly Mahony’s work.

Her arresting and unconventional style is immediately recognizable, but she also, for the first time, incorporated her initials into the design. By identifying herself as the author, Mahony challenged standard practices of a male-dominated profession in which only the signature of the principal architect is included on drawings. She wasn’t the first to do this, but signing the drawing suggests that Mahony understood her presentation drawings to be art objects in their own right, not merely representations of Wright’s architectural designs.

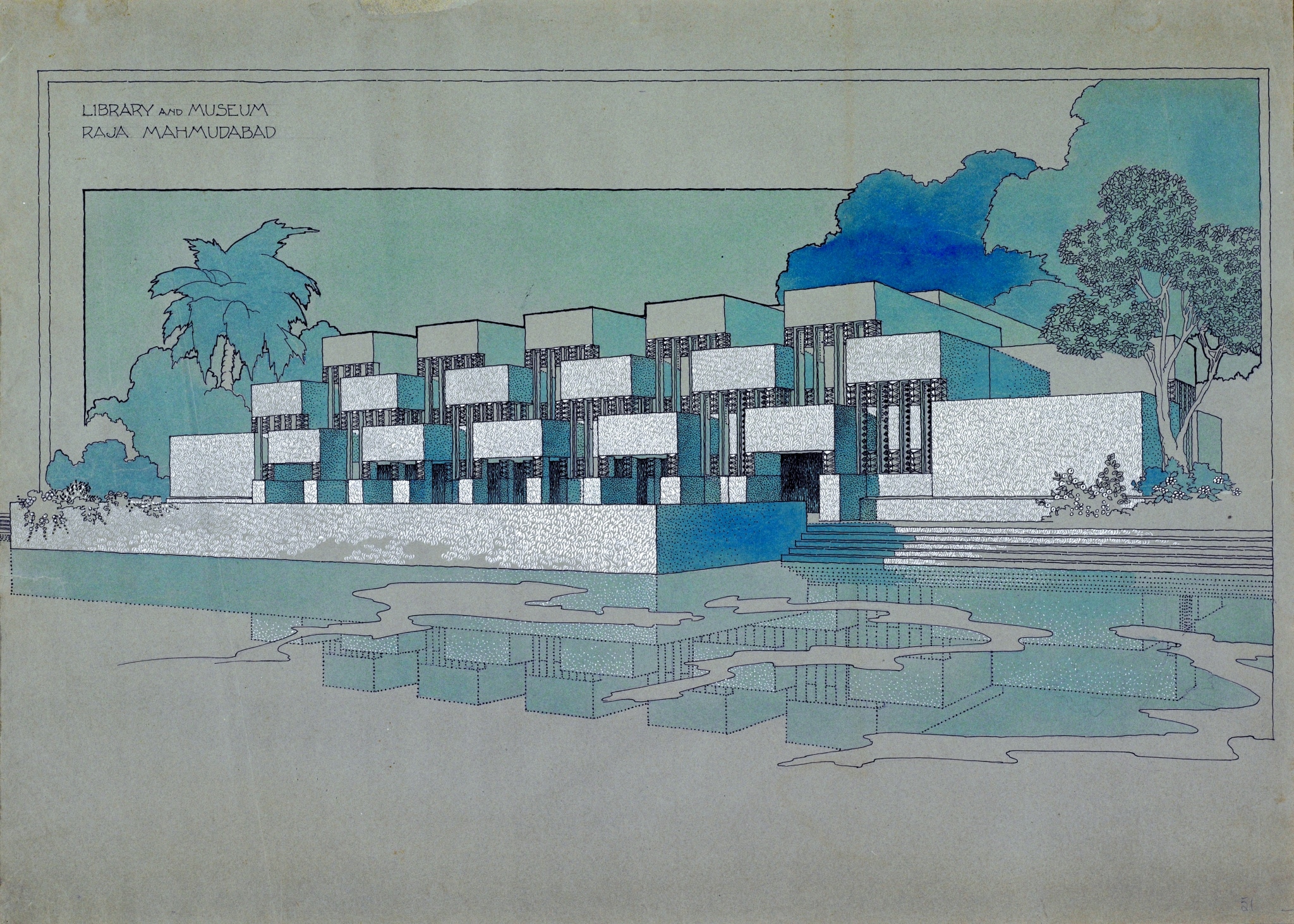

In 1911 Mahony married Walter Burley Griffin, another former employee of Wright’s, and started making renderings for their practice. This drawing for a library and museum is distilled to its essence. The reflection of the building in the water surrounding it is made only using dotted lines. Marion Mahony Griffin, renderer; Walter Burley Griffin, architect. Library and museum for the Raja of Mahmudabad, Mahmudabad, India. 1937. Perspective. Ink and watercolor on paper. Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin architectural drawings, 1909-1937.

It should be noted that perspective drawings such as Mahony’s are not used to construct buildings; they are used to show people untrained in reading plans, elevations, and sections what a building will look like. They are a type of marketing tool that would be shown to clients, exhibited in museums, and published in journals. In this context, Mahony’s unique and memorable drawing style provided Wright with a powerful brand identity for his practice. In 1911 Wright capitalized on this when he published a collection of fine-art lithographs illustrating his work. Known as the Wasmuth portfolio after its German publisher, the plates advertised his architecture—here redrawn in Mahony’s signature style to lend a consistent graphic identity to Wright’s practice—to European audiences, setting the stage for an increasingly global practice.5

What can we learn from Mahony about the role of women in architecture at the turn of the twentieth century? It can be argued that her practice—which centered on drawing, a more acceptable pursuit for women at this time, and visualized the designs of men—reinforced, to some degree, conventional gender roles.6 But her accomplishments are substantial given the gender bias of the architecture profession at the time she worked. Fellow designers, clients, and members of the building trades viewed women architects with suspicion, and few established architects were willing to take on women as apprentices, a cornerstone of architectural education. Wright’s Home & Studio in Oak Park was a laboratory for experimenting with new approaches to domesticity and work, and both Mahony and Wright came from a milieu that valued progressive education, democracy, activism, and gender equality. This created a space in which Mahony, for a time, could flourish and innovate.7

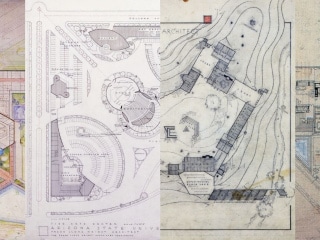

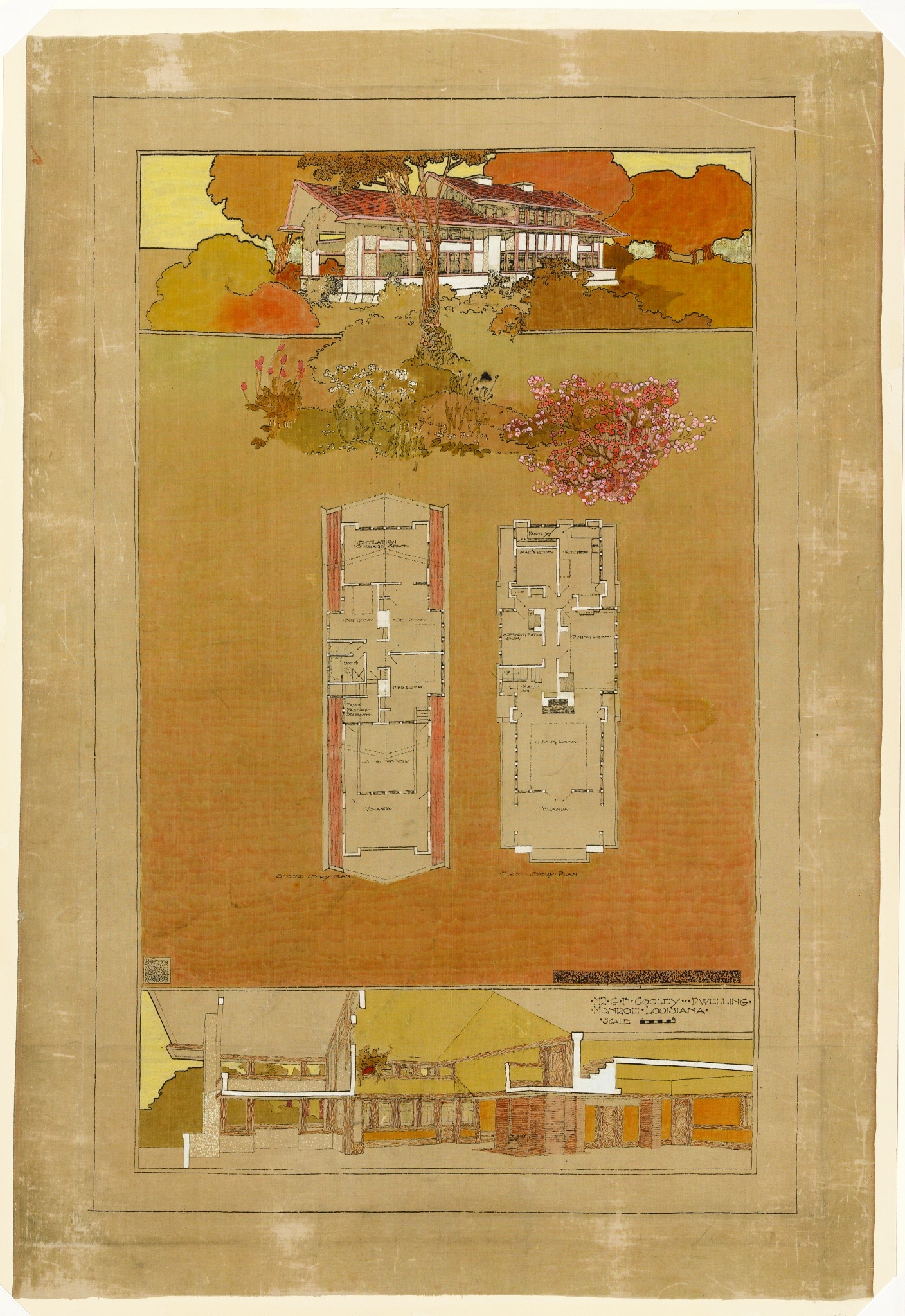

Around 1910, Mahony began experimenting with compositions that integrated plans, sectional perspectives, and exterior renderings, which allowed her to convey large amounts of information with the economy of a single drawing. Some of these, such as her drawing for the Cooley House, were transferred from linen to silk and embellished with ink washes, suggesting she understood these architectural drawings to be artworks or luxury objects, prized for their beauty and seductive pleasure rather than strictly technical characteristics. Marion Mahony, renderer; Walter Burley Griffin, architect. G.B. Cooley Dwelling, Monroe, Louisiana. 1910. Pen, black ink, and brown ink over graphite, with brush and colored ink, dyes and white gouache on beige silk. Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, gift of Marion Mahony Griffin, 1985.1.112. Sheet: 36 1/8 in x 24 3/4 in; image: 31 3/4 in x 20 3/16 in.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly. The Quarterly magazine is a member-exclusive benefit. To receive current and future issues, become a member today.

JENNIFER GRAY, Ph.D., is a noted Wright scholar who recently was the Curator of Drawings and Archives at Columbia University’s Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library. Dr. Gray was responsible for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, containing more than one million elements including Wright’s drawings, writings, and photography. Dr. Gray is also an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at Columbia and has taught at Cornell University and The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Dr. Gray was also the co-curator of the MoMA exhibition Frank Lloyd Wright: Unpacking the Archive. In addition to her expertise on Wright’s work, Dr. Gray’s research explores how designers, notably Dwight Perkins and Jens Jensen, used architecture, cities, and landscapes to advance social and spatial justice at the turn of the 20th Century. She also is interested in contemporary social practice, curatorial practice, the history of architecture exhibitions and questions of critical heritage. She will be leading the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation’s Taliesin Institute.

- Paul Kruty, “Graphic Depictions: The Evolution of Marion Mahony’s Architectural Renderings,” Marion Mahony Reconsidered, ed. David Van Zanten (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 43. Wright’s given name was Frank Lincoln Wright, but he later added Lloyd, his mother’s family name. For a period of time, he used both and signed his initials FLLW.

- Alice T. Friedman, “Girl Talk: Feminism and Domestic Architecture at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park Studio,” Marion Mahony Reconsidered, ed. David Van Zanten (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2011), 24-26.

- Kruty, 54-57, 63.

- Ibid, 66.

- Ibid, 78.

- David Van Zanten, Introduction to Marion Mahony Reconsidered (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2011), 16.

- Friedman, 26, 42-43.