Transcendental Spaces: Frank Lloyd Wright and John Lautner Through My Lens

Elizabeth Daniels | Jan 9, 2022

Architectural and editorial photographer Elizabeth Daniels reflects on an assignment to photograph John Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein Residence and the revitalizing nature of both Lautner and Frank Lloyd Wright buildings.

In 2011, I was sent on assignment to photograph John Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein House. Standing at its highest concrete edge, cantilevered over Bel Air, I gazed out at the breathtaking views of Los Angeles. Looking down into the canyon below, I was shocked to see my high school.

The realization that I’d passed my formative years oblivious to the existence of the extraordinary structure floating above me was enlightening. This epiphany was the beginning of my adventures channeling great architecture through my camera.

The rare perfect photograph is a talisman, capable of transporting me back to these peak experiences. Even a short visit to a Frank Lloyd Wright or John Lautner building inspires creativity and a feeling of freedom and strong individuality. Entering their spaces I feel like the star of a movie or the protagonist of a story about my life. It is no wonder Lautner’s clients often told him that people never want to leave his buildings.

When photographing structures designed by Wright or Lautner, my goal is to capture the energy these spaces contain. Before I understood their shared philosophy of Organic Architecture, I experienced similar, unique experiences in their spaces. I viscerally felt their connection.

Of all Wright’s apprentices, I believe Lautner most closely followed in Wright’s path. According to photographer Julius Schulman, Wright considered Lautner to be the “Next Best Architect on Earth.” Lautner thought Wright was a genius.

Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein Residence

Wright’s Charles Ennis House

To help me understand why these two architects’ work has such a profound impact on me, I spoke with Helena Arahuete who began working for John Lautner in her mid-twenties, shortly after immigrating from Argentina, and eventually becoming his firm’s lead architect for more than two decades. According to Arahuete, what mattered to Lautner was “designing like nature would design. Every part has a purpose and a reason.”

Frank Lloyd Wright’s theory of Organic Architecture drew inspiration from the mid-19th century Transcendentalist belief that nature is sacred and becoming one with nature is a path to the divine. The spaces Wright and Lautner created were built with a reverence to nature and are spiritually transformative by design.

In his 1939 book of lectures on Organic Architecture, Wright wrote, “In any good organic structure it is difficult to say where the garden ends and where the house begins or where the house ends and the garden begins… Buildings should love the ground they stand on.”

Organic Architecture incorporated ancient Chinese philosophy. Wright and Lautner often quoted Lao Tzu, author of the Tao Te Ching, to explain how their spaces were the essence of the structure. “The reality of the building consisted not in the four walls and the roof but inhered in the space within.”

In his monograph, John Lautner, Architect (1994), Lautner wrote “the purpose of Architecture is to improve human life… to produce timeless, joy-giving free spaces to fulfill ideally man’s needs—physical and spiritual, i.e. total.”

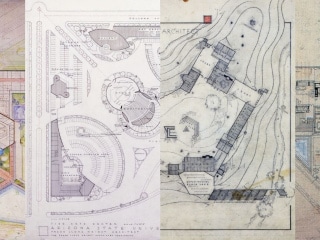

Wright’s Unity Temple

Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein Residence

Lautner’s Silvertop Residence

Wright’s Millard House (La Miniatura)

Both Wright and Lautner innovated technical solutions to address the challenges of each new topography.

Their Organic Architecture innovated ways to preserve nature, using raw materials to create natural extensions of the landscape. The timeless quality of nature is instilled in the structures.

Besides not copying Wright’s forms, Lautner practiced Wright’s principle of not repeating his own work. Each building is an original—yet, instantly recognizable.

While Lautner’s designs connect with Wright’s Prairie style designs more than with the textile block houses, the principles of Organic Architecture are woven into Wright’s entire body of work. Both Wright’s La Miniatura, and Lautner’s Silvertop were constructed around trees. In a 1978 lecture, Lautner describes leaving Silvertop “open through to the mountains… the hilltop completely free so it’s a private glass dune.”

In Lautner’s Sci Arc lectures (1978 and 1991), the student architects in attendance laugh incredulously as slides of his breathtaking buildings flash in front of them. When the pool at Silvertop is shown, there is audible shock. One of the first infinity pools ever built, this was Lautner’s solution to integrating water visually into the landscape. Water was used like a raw material, the resulting innovation preserves its essence.

Wright’s George Sturges House

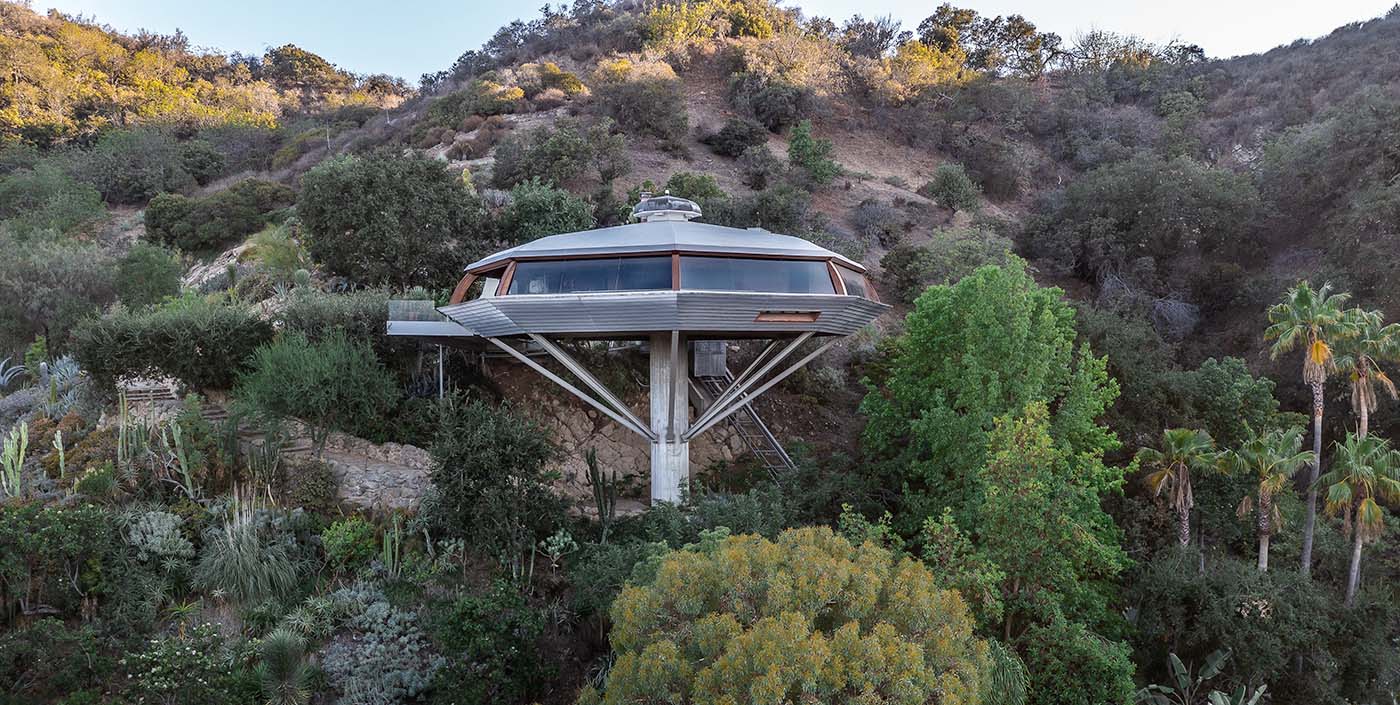

Lautner’s Chemosphere

Lautner was project superintendent for the building of Wright’s Sturges House. Then 28 years old, Lautner was by this time beginning to come into his own. Imposingly tall and low-key, he would collect Wright from the airport and escort the flamboyantly attired Wright around Los Angeles. On one such trip, Lautner proudly showed his mentor a compact residence in the Silver Lake Hills. This was the inception of his practice.

The Sturges was built on a concrete and brick support to preserve the land. Twenty-one years later, Lautner’s Chemosphere went up with the same idea using a different support. Both buildings are cantilevered above sites that would otherwise have been bulldozed to be built on. Comparing these houses demonstrates Lautner’s mastery of Organic Architecture and the evolution of his individuality.

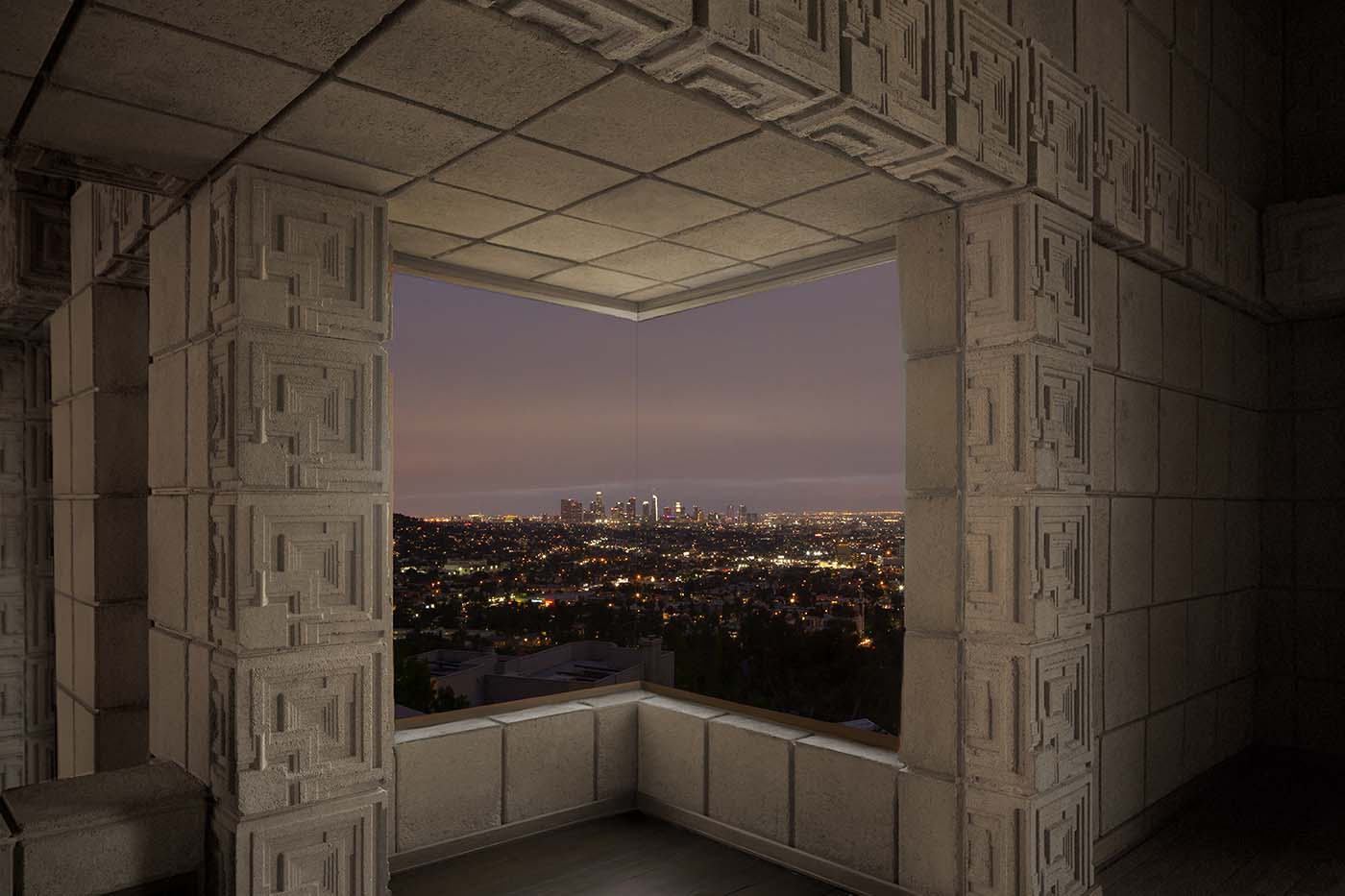

Both architects built with one central idea for each project. Wright’s Ennis and Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein are both built to frame views of the Los Angeles skyline, visible from every room. This is done so well that the views seem built around the houses.

Lautner said that for every aesthetic decision there were ten technical ones. Every choice was deliberate, and technical problem-solving was part of the job.

Wright was one of the first to use corner windows. Lautner evolved the corner windows into hanging glass walls. The cantilevered master bedroom in the Sheats-Goldstein House comes to a point at a glass corner that opens with the touch of a button.

In the living room, 750 glasses are built into the concrete ceiling. Lautner, in the Bette Jane Cohen film The Spirit in Architecture (1990), says “the idea for the living room was to get perforated light like you get in a primeval forest.”

In his Prairie School masterpiece Unity Temple, light filters through twenty-five golden skylight windows Wright says, “to get a sense of a happy cloudless day into the room… daylight sifting through between the intersecting concrete beams, filtering through amber glass ceiling lights. Thus managed, the light would, rain or shine, have the warmth of sunlight.”

Lautner’s Hope House

Lautner’s Hope House in Palm Springs is an extension of the desert around it. The entrance is built around gorgeous rock formations, a striking visual expression of Organic Architecture.

The concrete pillars of the Hollyhock House, based on the structure of the hollyhock flower and Mayan designs, instill an ancient spiritual feeling into the space. When I was alone on the rooftop at sunset, experiencing breathtaking views with the Ennis hanging over the city in the distance, it was like seeing Chichen Itza in the rain.

Lautner’s LaFetra-Stevens House

Wright’s Hollyhock House

The LaFetra-Stevens House is a masterclass of Lautner’s incomparable ability to incorporate numerous requests of his client while also fitting into the surrounding landscapes of the mountains and ocean. It is a sculpture, visually arresting to anyone walking down the beach, or lucky enough to experience the interior.

I love watching the light change throughout the day, which changes the personality of the architecture. At night the houses can be mysterious, almost terrifying in their pitch black shadows. The days and nights I have spent photographing these spaces have been the most exciting adventures of my life.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2021 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly. The Quarterly magazine is a member-exclusive benefit. To receive current and future issues, become a member today.

Elizabeth Daniels at Wright’s Ennis House

ELIZABETH DANIELS is an architectural and editorial photographer based in Los Angeles. You can find her on Instagram at @elizabethdaniels01.