Seven Hidden Gems from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Period

Amy Beth Wright | Aug 7, 2017

Just as it seemed that Wright’s pivotal design years had past, Wright entered into two prolific decades of innovation (1936-1959) in his mission to design the ideal American home.

This article was originally published on Metropolis magazine online, and is used with permission.

The word “Usonian” (United States of North America) is attributed to writer James Duff Law, who wrote in 1903, “We of the United States, in justice to Canadians and Mexicans, have no right to use the title ‘Americans’ when referring to matters pertaining exclusively to ourselves.” Wright referenced this quote, misattributing it to writer Samuel Butler in Architecture: Selected Writings 1894–1940: “Samuel Butler fitted us with a good name. He called us Usonians, and our Nation of combined States, Usonia.”

Wright designed his first Usonian home in 1936, when Milwaukee Journal writer Herbert Jacobs challenged him to design a house of good quality that cost no more than $5,000. Similar to the homes for Broadacre City, a utopian model for an American community that Wright completed with Taliesin apprentices in 1934, the Jacobs house embodies Wright’s notions of an ideal home set within the American landscape. Just as it seemed that Wright’s pivotal design years had past, the Jacobs House commenced two prolific decades of innovation (1936-1959), which we now refer to as Wright’s Usonian period.

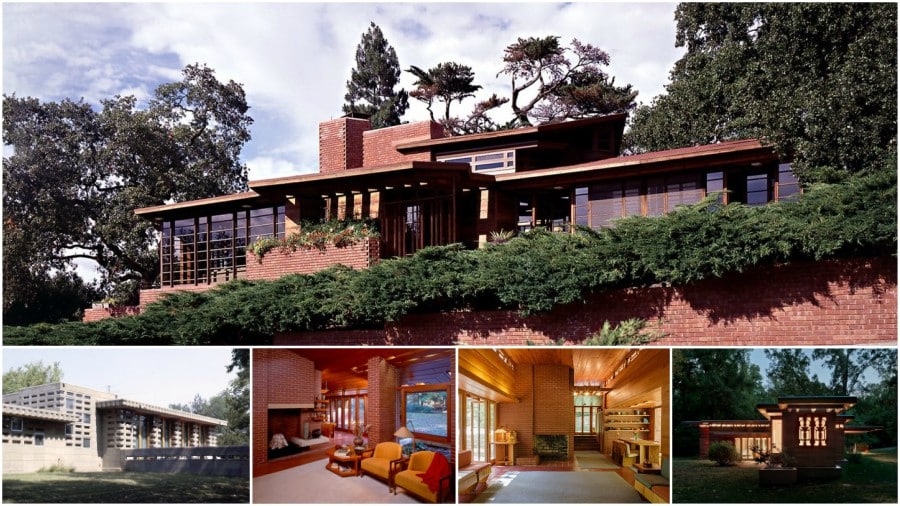

Design elements for these single-story homes include: flat roofs with generous overhangs and cantilevered carports (Wright coined the term carport, and favored these over garages for efficiency), built-in furniture and shelving, tall windows that softened the boundary between interior and exterior, radiant heat embedded in a concrete slab gridded floor, skylights, a sense of flow from one room to the next, and a central hearth. Floor plans dispensed with basements, attics, and, in smaller models, formal dining rooms to maximize efficiency. Typically situated on inexpensive and remote sites, away from major urban centers, and set back from the road, Usonian homes nestled into their surrounding landscapes. Wright used local materials, experimenting with combinations of wood, glass, and masonry. These homes indicate Wright’s responsiveness to his client’s interests as well as interest in simplicity, connection to the land, and efficiency. The following seven homes express the principles Wright developed for the Usonian model, as well as the many innovative variations he imagined in collaboration with clients.

Hanna House (1936), Stanford, California

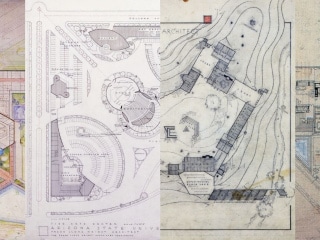

Over the course of a twenty-five year collaboration with Stanford professors Paul and Jean Hanna, Wright ultimately created an open plan absent of right angles for his house by integrating hexagonal modules that gradually expand the floor plan. When finished, the house included a hobby shop, guest house, storage room, double garage, and garden house, and exceeded the typical Usonian home in both size and cost. The use of geometry to create an open floor plan foreshadowed Wright’s approach to designing the Guggenheim Museum, seven years later. The Hannas donated the house to Stanford University in 1975.

Pope-Leighey House (1940) Alexandria, Virginia

To create a sense of spaciousness for the Pope House, built for journalist Loren Pope and his wife Charlotte, Wright employed the technique of compression and release, where a smaller room or foyer leads directly to a much larger room. The Pope’s budget was less austere than the Hannas, and their Usonian spanned 1,200 square feet; to further suggest expanse, Wright designed the eaves to be broadly cantilevered. The Popes sold their home to Robert and Marjorie Leighey in 1946, and Marjorie Leighey donated the site to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1965, when it faced demolition due to a planned expansion of Highway 66. The National Trust relocated the house to the same site as Woodlawn, an estate that was once part of George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Both Woodlawn and the Pope-Leighey are open for tours, and a combination ticket to tour both sites is available. The house was moved again in 1995, thirty feet uphill, to situate it on more stable soil.

Affleck House (1941) Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

When Detroit-based Gregor and Elizabeth Affleck reached out to Wright in 1940, he advised by post that they “go far out of the city and find a site nobody wanted or could build on.” The primary unit room of the Affleck House overlooks a forty-foot ravine, and the house is set within a hilly landscape. Significant features include 600 feet of built-in shelving and a planter box atrium in the center of the home that looks down on a reflecting pool below. An aperture in the atrium can be released to allow cool air into the house. The exterior is built from tidewater cypress and brick, and the interior walls are three-quarter-inch plywood set between overlapping tidewater cypress planks.The Affleck’s children donated the house to the College of Architecture and Design at Lawrence Technological Institute in Southfield, Michigan; tours are available once a month.

Zimmerman House (1950) Manchester, New Hampshire

Wright designed this 1,458 square-foot home on a continuous concrete mat, and also designed many of the ancillary elements, such as the gardens, furniture, dinnerware, and mailbox. Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman bequeathed their Usonian house to the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester in 1988. It is one of a few Wright-designed sites that is integrated within an art museum, and much of the Zimmerman’s extensive collection of pottery, sculpture, and paintings is on display; tours can be arranged through the Currier website.

Tonkens House (1954) Cincinnati, Ohio

In 1949, Wright patented the technique of interlocking concrete blocks together and reinforcing them with horizontal and vertical rods set into the walls and roof (along with a grout mixture between the rods and blocks). Both the blocks and the homes they created were termed “Usonian Automatics.” The Tonkens house is a Usonian Automatic north of Cincinnati that “incorporates eleven different patterns of concrete block, and over 400 inset windows,” writes the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Though listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the house is privately owned, sold by Beverly Tonkens in 2013.

Gordon House (Designed in 1957, completed 1964) Silverton, Oregon

The Gordon House, adjacent to the Oregon Garden in Silverton, was completed after Wright’s death under the supervision of Taliesin apprentice Burton Goodrich. As some other Usonians (including the Pope-Leighey), it emphasizes a form of perforated woodwork called “fretwork,” as well as numerous inventive storage solutions to offset the absence of a basement or attic. It was based on a 1938 design that Wright completed for Life magazine. The site is currently under the auspices of the Gordon House Conservancy and, in addition to tours, hosts a vibrant pedagogical program in collaboration with local educators.

Sharp Family Tourism and Education Center (Completed 2013, designed in 1939) Lakeland, Florida

The largest collection of Wright buildings on one site is located on the campus of Florida Southern College in Lakeland, Florida. Between 1938 and 1958, twelve of the twenty buildings that Wright envisioned for the college were completed. In 2013, Jeffrey Baker of Albany-based firm Mesick, Cohen, Wilson, Baker Architects oversaw construction of a thirteenth property, a Usonian house based upon a 1939 Wright design for a faculty house. The house is now home to the Sharp Family Tourism and Education Center, which interprets and educates visitors on Wright’s legacy on the campus.

All photography of the center courtesy © Miseck Cohen Wilson and Baker / Florida Southern College