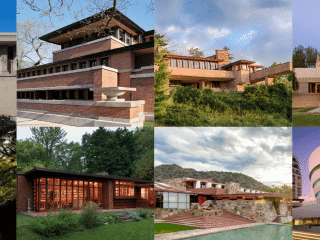

Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings Worthy of a Road Trip

Design Milk | Jul 17, 2017

Consider a road trip for a safe way to get out and travel. Design Milk created a list of Frank Lloyd Wright properties to help you plan an architectural adventure.

This article originally appeared on Design Milk

This year marks the 150th anniversary of Frank Lloyd Wright’s birth. Everyone from designers to Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation president & CEO, Stuart Graff, have suggested that the best way to learn about the lasting impact Wright has had is to experience a Frank Lloyd Wright site in person. Considering that Wright designed more than 1,000 structures, you’d be forgiven for feeling a little overwhelmed with the possibilities. So, together with The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, we’ve come up with nine Frank Lloyd Wright buildings open to the public across the United States that will make you want to see more.

Ready for an architectural road trip? Although iconic buildings like Fallingwater and the Guggenheim, should certainly be on your bucket list, these picks are definitely detour worthy. We couldn’t possibly choose favorites, so the list is alphabetical. Map out your closest Frank Lloyd Wright site and get going!

Remember to contact Wright sites directly in advance of your visit. Due to the ongoing COVID pandemic, many sites that are typically open for public access or tours may be experiencing intermittent closures or limited availability.

More Frank Lloyd Wright sites can be found here: FrankLloydWright.org/Work.

A.D. German Warehouse (Photo by Teal Tizzy Photography)

What: A.D. German Warehouse

Where: Richland Center, WI

Completed: 1921

Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in his birth town of Richland Center, WI, this impressive building has often been compared to a Mayan Temple. The only warehouse designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, this avant-garde storage space was built for a local businessman’s grocery business. It’s one of the earliest examples of a poured concrete construction, the entire 4,000 square foot building rests on a pad of cork for stability and shock absorption. Experimentation is never inexpensive, and the A.D. Warehouse was no exception. Construction was stopped, with the building unfinished in 1921 after spending $125,000, which exceeded the original cost estimate of $30,000.

Front exterior of Bachman Wilson House at Crystal Bridges (Photo by Nancy Nolan Photography)

What: Bachman Wilson House

Where: Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Completed: 1956

This house is an example of the type of architecture that Frank Lloyd Wright called Usonian. He used the word to describe a New World style of building that was free from previous conventions. This house was originally built for Gloria and Abraham Wilson in 1956 along the Millstone River in New Jersey. It was subsequently purchased by architect/designer team Lawrence and Sharon Tarantino in 1988 and meticulously restored. When the house was threatened by repeated flooding at its original location, the Tarantinos determined that, in order to preserve it, they should sell the house to an institution willing to relocate it. After the Tarantinos conducted a multi-year search for a suitable institution, Crystal Bridges, an art museum in Arkansas, acquired the house in 2013. The entire structure was then taken apart and each component was labeled, packed, and moved to Arkansas, where it was reconstructed in 2015.

Charnley-Persky House East Elevation (Photo by Leslie Schwartz)

What: Charnley-Persky House

Where: Chicago, IL

Completed: 1892

Designed by famed Chicago architect Louis Sullivan of the firm Adler & Sullivan in 1891-1892, the the Charnley-Persky House is notable as one of the few extant buildings that display the combined talents of Louis H. Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, his then-draftsman. The house embodies Sullivan’s desire to develop a new form of American architecture that would break with the past and would express new American values and ideals. Frank Lloyd Wright called it “the first modern house in America.” It would become the basis for Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie style and heralded a fundamental shift in architectural style.

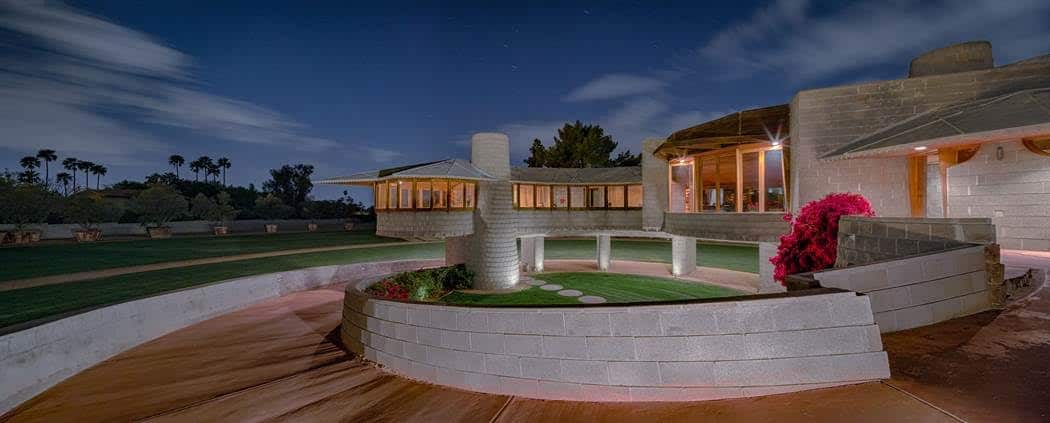

David Wright House (Photo by Andrew Pielage)

What: David Wright House

Where: Phoenix, AZ

Completed: 1952

The David Wright House is regarded as one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s late-career masterpieces. Its spiral design foreshadows the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Frank Lloyd Wright noted that the views over the trees were more dramatic than those within the grove itself, so he used a single bold spiral gesture to visually pull the house towards the sky, lifting it above the treetops and away from the dusty desert floor. Wright called this home “How to Live in the Southwest.” It was designed and built of concrete blocks, wood boards, and sheet metal – common materials brought together in a lyrical composition, serving as a metaphor for the potential of American democracy when built on the shoulders of the common man. The building has not yet been recognized as a historical landmark as it was rescued from demolition by private individuals.

Marin County Civic Center (Photo by Jeff Wong)

What: Marin County Civic Center

Where: San Rafael, CA

Completed: 1962

This was Frank Lloyd Wright’s last and largest public project. After the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge in 1937, the Civic Center was intended to connect Marin County and San Francisco as well as to consolidate county services. Frank Lloyd Wright was selected following a rigorous interview process that evaluated 36 architectural firms for the job. Of all the architects interviewed, only Frank Lloyd Wright saw possibilities in the hilly landscape of the site. All other architects suggested flattening them. Not only did the innovative building respond organically to the site, but it’s now also considered by historians to be one of the first public buildings to incorporate the automobile into its design. Visitors drive through the building’s arches and the parking lot is created as part of the landscape plan. And, in another nod to car culture, Frank Lloyd Wright sited the buildings so one can get a “snap shot” view from the highway driving by at 55 mph. The Civic Center is both a state and National Historic Landmark, designated in 1991.

Martin House Conservatory Interior (Caitlin Deibel)

What: Martin House Complex

Where: Buffalo, NY

Completed: 1905

Built for wealthy Buffalo businessman Darwin D. Martin, this residence is more than just a house, it’s a complex of six interconnected buildings. The main Martin House and a pergola that connects it to a conservatory and carriage house with chauffeur’s quarters and stables, the Barton House, a smaller residence for Martin’s sister and brother-in-law, and a gardener’s cottage added in 1909. Despite its massive size, Martin’s wife, Isabelle, was unhappy with house. She had limited sight, and the lack of natural light in the building only decreased her visibility. Despite her displeasure, this remained the family home for decades. A millionaire, Darwin was nearly wiped out by the 1929 stock market crash and following his death in 1935, the family was forced to abandon the property.

It is the most substantial and highly developed of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie School style houses in the Eastern United States and received National Historic Landmark Status in 1986.

Monona Terrace

What: Monona Terrace Community and Convention Center

Where: Madison, WI

Completed: 1997; Wright’s time on the project 1938-1959

This building was a true labor of love. Frank Lloyd Wright’s first design for Monona Terrace was created in 1938. He spent 21 years, 63,000 hours of staff time, drew some 4,000 sketches and eight drafts for the project, which was finally completed in 1997, almost 40 years after his death. Although the exterior remains true to Wright’s design, the interior was reworked by a Wright protégé, Tony Puttnam.

Wright’s design plan was inspired by two key elements of the unique site: the nearby State Capitol and the waterfront. Wright’s trademark features of dramatic open spaces, strong geometric forms, and breathtaking views have made this building a Madison attraction. It still hosts more than 600 events each year.

Pope-Leighey House

What: Pope-Leighey House

Where: Alexandria, Virginia

Completed: 1939

Like the Bachman Wilson House, this is one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian homes, his concept for providing affordable, yet aesthetically pleasing, homes. Many of Frank Lloyd Wright’s innovations for the home, including spacious interiors, corner windows, and a cantilevered roof, became part of the American design vernacular. The house was built in response to a 1939 letter sent to Frank Lloyd Wright from Loren Pope, a 28-year-old copy editor for Washington, D.C.’s Evening Star newspaper. Together with his wife, Charlotte, they had just purchased a plot of land. “Dear Mr. Wright,” he wrote. “There are certain things a man wants during life, and, of life. Material things and things of the spirit. The writer has one fervent wish that includes both. It is for a house created by you.”

The budget was $5,000. Fifteen days later, Frank Lloyd Wright responded, “Of course I am ready to give you a house.” In March 1941, the couple moved into their new 1,200 square-foot, Wright-designed home.

In 1965, the house was relocated to the grounds of the 126-acre estate that was originally part of George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Today, the Pope-Leighey House is owned and operated by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

What: Burton and Orpha Westcott House

Where: Springfield, OH

Completed: 1908

Completed in 1908, The Westcott House is Frank Lloyd Wright’s only Prairie Style home in Ohio. Its history is a tumultuous one – shortly after WWII the house was divided into apartments and subsequently stripped of many of its original features. It served as an apartment complex for over half a century – its sleeping porches were turned into kitchens, pony stables into a shower stall, and its original garage that used to store the Westcott Car, into a game room with a pool table in the middle, right by what used to be a mechanic pit. In the 1990s the house was quickly deteriorating and, as Matt Cline, a site manager noted, the house seemed to be “held together with duct tape, bubblegum and a few prayers.” In 2005, the Westcott House underwent an inch-by-inch $5.8 million restoration. All the dramatic and unfortunate changes were reversed. The Westcott House was lucky – there were still close to 50 original drawings stored at the Frank Lloyd Wright archives and these drawings helped to bring the house back to its original glory. Today Westcott House is on the National Register of Historic Places.

You can find more public Frank Lloyd Wright sites at: FrankLloydWright.org/Work.

Remember to contact the Wright sites directly in advance of your visit. Due to the ongoing COVID pandemic, many sites that are typically open for public access or tours may be experiencing intermittent closures or limited availability.